Prisons, Panopticons and Dobson’s Plans

“I feel no hesitation in saying, that there is not a gaol in Great Britain so admirably calculated to effect all the important objects of prison discipline, and more especially those of separation and classification, as that proposed by Mr. Dobson.”

In order to better understand John Dobson’s plans for Newcastle prison it is helpful to understand the context in which they were built.

JOHN DOBSON

(1787-1865)

John Dobson was an architect born in North Shields and based in the North of England. He had a prolific career, designing over 50 churches and 100 houses. He is perhaps best known for his work with Richard Grainger that helped redevelop the centre of Newcastle in the neoclassical style. Dobson was the architect responsible for the building of Newcastle’s Carliol Square Gaol in the 1820s and also designed Morpeth gaol in this same period.

Dobson’s earliest designs, produced around 1822, included radiating wings around a central column. Dobson’s decision to build in this style was very much in keeping with the Benthamite principle of the Panopticon.

Jeremy Bentham was a renowned English philosopher and theorist of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, perhaps most famous for his work on Utililtarianism and the notion of the “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” being the fundamental measure for societal right and wrong. However, amongst his many ideas was a style of institutional building design known as the panopticon. From the Greek ‘Panoptes’ meaning all seeing, the Panopticon was primarily designed to allow a single observer (be that a governor or security person) to be able to theoretically observe all of the inmates of the prison at anyone time. This would effectively engender a feeling amongst the prisoners that they were under constant surveillance and thus would have to regulate their behaviour accordingly. Although the prison is the perhaps the most well-known of its applications, Bentham believed the Panopticon design could be applied to many different institutional buildings (from schools to sanitoriums).

For all his impact in the period, very few prisons were actually built in a style that was entirely true to the Benthamite Panopticon principal. One notable example was Millbank Prison in London, opened in 1816. However, many adopted elements of his principal, one such architect being John Dobson.

Testament to the popularity of Dobson’s Benthamite ideas can be seen in some of the contemporary notes of praise from leading prison officials and architects that Dobson’s early plans received. Amongst these responses was one from Captain James Brown, Edinburgh, who was effusive in his praise, "I feel no hesitation in saying, that there is not a gaol in Great Britain so admirably calculated to effect all the important objects of prison discipline, and more especially those of separation and classification, as that proposed by Mr. Dobson." Similarly, the governor of Edinburgh Gaol, Mr Young, believed that, “His (Dobson’s) designs secure all the important points in prison discipline, security, classification, and inspection, and completely guard against the possibility of combination." The Gaoler of neighbouring Durham Gaol, John Wolfe, was equally impressed arguing that Dobson’s plans were “an improvement upon the best plans I have had an opportunity of seeing."

Writing in 1827, a year before the gaol’s completion Historian Eneas Mackenzie argued that Dobson’s plans had been built around the following three principles, all of which pay homage to Bentham’s principles. “1st, for the safe custody of the prisoners; 2dly, for their punishment; and, 3dly, for their reformation. By erecting a circular or elliptical building for the residence of the keepers, from which they can at all times unseen inspect the radiating wings of the prisons, the barbarous contrivance of dungeons and fetters become unnecessary, and misbehaviour cannot elude observation and instant correction.”

Dobson’s decision to build radial wings around a central observation point was very much in keeping with the Benthamite principle. Further to this Dobson was particularly keen to avoid any interaction between visitors and the set-up of the cells in single file units was designed to achieve this. “By erecting a circular or elliptical building for the residence of the keepers, from which they can at all times unseen inspect the radiating wings of the prisons, the barbarous contrivance of dungeons and fetters become unnecessary, and misbehaviour cannot elude observation and instant correction.”

Dobson was particularly keen on the separation of prisoners and the individualisation of cells. The committee of the “Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline” had put forward the recommendation of wings that would include a double row of cells, but Dobson stood firm on his decision to only include a single row of cells. He was particularly keen to separate prisoners and to avoid all potential for interaction, seeing it as leading to corrupting behaviour. “In this building, each wing contains but a single row of cells; and the windows are opposite to the blank, back wall of the next wing, so that no telegraph conversation can be held between the different classes, who will be as completely separated from each other as if they were.”

“The grand object is to make labour a source of pleasure. This, it is said, might be effected by lodging criminals in small, secluded cells, and feeding them with the very coarsest bread and water: but if they volunteer to work, to allow them a portion of their gains to purchase greater comforts; the co-operation of the governor being obtained, by permitting him to share in the produce of their labour.”

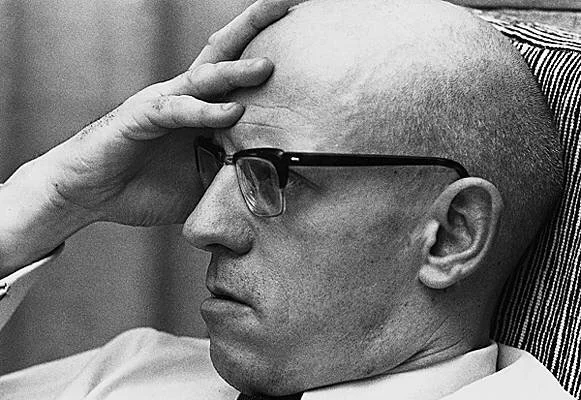

Bentham’s Panopticon had something of a resurgence when it became the focus of French Philosopher Michel Foucault’s groundbreaking work Discipline and Punish. In it Foucault argued that the principle behind the design spoke of something far wider than prison architecture itself. He saw in the Panopticon a model for the power structures within modern society and coined the term ‘Panopticism’, utilising the Bentham principle, to indicate a new sort of system of internal surveillance. He described this as a system of disciplinary power and observed how it was fundamentally different from what had gone before.

Michel Foucault - Discipline & Punish

“Traditionally, power was what was seen, what was shown, and what was manifested...Disciplinary power, on the other hand, is exercised through its invisibility…In discipline, it is the subjects who have to be seen. Their visibility assures the hold of the power that is exercised over them. It is this fact of being constantly seen, of being able always to be seen, that maintains the disciplined individual in his subjection.”

Following on from Foucault, some have argued that we see the remnants of Benthamite Panotpicon theory to this day through, amongst other things, CCTV and social media; both creating a sense in which your actions are being observed or potentially observed at all times, by an unknown watcher, thus creating a system of self regulation.

Bentham died in 1832, a few years after the completion of Newcastle Gaol, however he left one remarkable request in his will that perhaps pays testament to his panopticon principle of constant observation. As part of his dedication to the utilitarian principle he donated his body to science and gave the additional request for his head and body to be preserved; a request that was duly met. Now referred to as his ‘Auto-Icon’ the box containing his body was even used as part of a surveillance experiment undertaken by University College London’s (UCL) Digital Centre for Humanities in 2016 entitled the Panopticam. In 2020 it was given a permanent home at UCL’s Student Centre.