“It is strange, but in one custom we are more barbarous than our ancestors in bygone days. It is the toll of the Felon’s Plot.”

- The Nottingham Evening Post, 24th Oct, 1925.

Prison Burial

You might think that being executed would be punishment enough for an awful crime, but as late as the twentieth century in Britain there were what was known as post-mortem punishments. The most common two punishments were public dissection (anatomisation by surgeons) and gibbetting (the criminal’s body was encaged in iron and hung from a wooden mast, most commonly placed near the site of the crime or in a very prominent location as near to it as possible). Post-Mortem punishments have a long history, but arguably the longest lasting was the denial of a Christian burial and the refusal of the authorities to hand the convicted felons’ body over to their loved ones for burial. This punishment continued long after dissection and gibbeting were removed by the Anatomy Act (1832) and Hanging in Chains Act (1834) respectively.

We know from reports of executions in Newcastle that sometimes the fear of indecent burial was more potent than that of hanging itself in the minds of prisoners. In 1829 one broadside recorded Jane Jameson’s last moments before leaving the gaol on route to the gallows at the Town Moor. It noted that she asked the attendant Minister ‘a question about her body’, but was told that ‘she was not to care about her body but about her soul.’ Jane Jameson became the last executed felon in Newcastle to suffer the additional punishment of public dissection, but her body was not buried in the gaol grounds.

A fate worse than death.

Burial within the prison walls

The first person to be buried within the walls of the Prison was Mark Sherwood in 1844. Although executed on Newcastle’s Town Moor his body was taken back to the prison via a carriage and interred within the boundaries of the prison. Like Jane Jameson before him Sherwood had raised concerns about what would happen to his body after death. Reports of his execution noted that one of his last requests was that “He expressed a wish that for interment of his bodily remains within the gaol-yard, the grave might be deep, and hoped his remains would not be allowed to be disturbed. He also desired, if not contrary to any legal regulation, that the burial service might be read when he was committed to the earth. In compliance with his wish the grave was made seven feet deep, as subsequently stated but the burial service was not read.”

Sherwood’s fears of being disturbed were not without justification as up until the Anatomy Act, 1832, the only bodies officially available for dissection, without consent, were those of executed criminals. This limited supply meant that across the country there were numerous instances of body-snatchers, sometimes known as resurrectionists, operating in churchyards and cemeteries. Newcastle was no exception. This illegal practice, arguably made most famous by William Burke and William Hare in Scotland, came about to meet the demands of a medical profession starved of body supply. Just 3 years prior to Sherwood’s execution Newcastle had been gripped by a body-snatching scandal very close to the prison. In 1840 Sophia Quin had died in the house of her daughter, Rosanna Rox, in Clogger’s Entry in Sandhill, Newcastle and was due to be buried at the dissenter’s burial ground at Ballast Hills, to the East of the city. Instead of going to the burial ground the coffin bearers took the body straight to the Surgeons’ Hall and refused Rox entry. She later gained entry by contacting the Mayor and found her mother’s coffin with the lid up and clothes were torn. On further investigation, they lifted the lid of what appeared to be a large chest and found her mother’s body standing upright in warm water up to her shoulders. At which point Rox fainted. The body was eventually recovered and successfully reburied but, it caused a great scandal in the region and was even reported on in the Medical Journal, The Lancet.

Until its closure in 1925, 15 executed criminals were buried within the walls of the prison and in most cases denied a Christian burial. After an execution it was customary for the body to hang for one hour, a centuries-old tradition, and then for an inquest to take place on the body to confirm both the cause of death and identity of the condemned. The burial would take place the same day, following the inquest over the body, and in the presence of the Prison Chaplain and a few officials.

Numerous reports from executions in the period note that there were markings made with the initials of the prisoners on stones in the boundary walls, relating to the position of their grave, but little else marked their presence. Indeed, such was the disdain for the recording or memorialising of criminal bodies in any way that a Home Office Circular in 1922 demanded that even these markings were to be removed as “such records are undesirable as they perpetuate the memory of the crime, cause unnecessary pain to relatives and rouse a morbid interest in the prisoners.” One proviso of this decision was that each prison was required to make a detailed map of the location of the bodies before destroying these remaining memorials.

Despite the Home Office’s request the location of the bodies became a serious problem for the authorities on closure of the prison. In agreeing to allow Newcastle to demolish and repurpose the prison land, the Home Office stipulated that the bodies must be removed and reinterred. Numerous reports abounded that the authorities were struggling to locate the exact placing of each grave and indeed when it came to the operation to remove them a number of bodies weren’t found. Up until now the identity of these bodies has been unknown, but research seen by this project has uncovered the identity and number of the missing bodies at Newcastle Prison.

“In the darkness of the night and at an hour kept strictly secret the bodies of the murderers which lie in the precinct of Newcastle Gaol are to be taken up and reinterred in All Saints’ Cemetery.”

Removing the bodies: On the closure of the prison

On Monday 12th October, 1925 the Governor of Durham Prison along with Robert Stuart, the medical officer and prison surgeon was in attendance at the exhumation of the graves. Stuart made a detailed report of his findings that was sent on to the Home Office. In it he gave key details into how the bodies had been buried, including whether they were clothed or not and the state of decomposition. Amongst his recordings was the following extraordinary details.

· 1. Mark Sherwood – 1844 “At a depth of about 11 feet there was no trace of coffin or body”

· 2. Patrick Forbes – 1850 “At a depth of about 11 feet there was no trace of coffin or body”

· 6. William Rowe (sic) – 1890 “We found no trace of body or coffin in this grave”

· 7 Samuel G Emery – 1894 “At a depth of about 11 feet we found no trace of a body in his grave.”

So, not only were the bodies not found but also, in some cases the coffins weren’t even located. It would appear that Mark Sherwood’s fears weren’t so ill-founded. Despite only locating 11 of the 15 bodies, the remains were eventually buried in unmarked graves at All Saints Cemetery in Jesmond – such was the secrecy around their location, that it is still unknown to this day.

Reporting on the reinterment one newspaper carried a telling quote from an unnamed prison official at Newcastle Prison,

“It is strange, but in one custom we are more barbarous than our ancestors in bygone days. It is the toll of the Felon’s Plot….Prison Officials who have assisted in the last act of a murder drama will agree that it is a mournful business. The body lies in its plain shell- not naked and covered with quicklime as was the custom until quite recent years – it lies clad in the clothes worn at the trial, so that no sensation-monger may exhibit them….when the grave is filled in the ground is levelled with its extremities marked by small white stones. On the wall of the prison that is nearest to the plot will be cut the initials of the dead and the date of the execution.”

However, there is one final twist to the tale that has been uncovered in the research for this project. On September 1st, 1928 The Boston Guardian carried the following remarkable story,

“Remains of a man who had been executed were found during excavation work for an automatic telephone exchange on the site of the old Newcastle Gaol.”

This may well tally with one of the memories that was sent in to us from a member of the public, Marie McNichol. Marie McNichol’s grandfather John (Jack) Level was part of the demolition and excavation team working on the prison site. He was employed by Purdie, Lumsden & Co as a Derrick Crane operator. Marie remembers that the building work was severely delayed when a body was uncovered “wrapped in oilskins, like that of a sailor.” An investigation followed that delayed the excavation work considerably and on the 27th August the Yorkshire Post reported that the body had remained unidentified but “It is believed the remains are those of another executed man. The bones were reinterred at Jesmond on Saturday.”

According to Marie, though, there was a much more extraordinary find to follow, one which was never reported. To find out what see here.

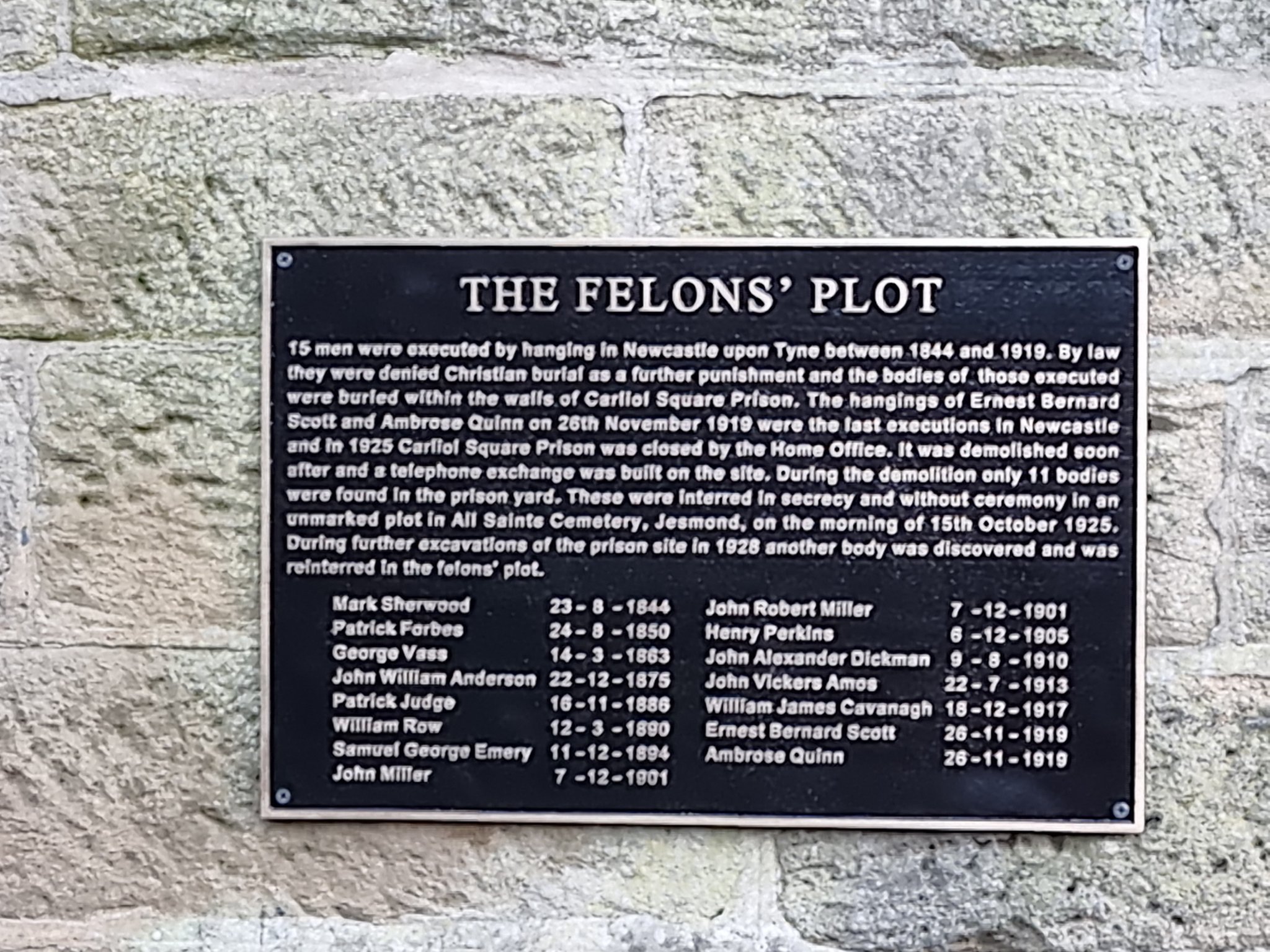

Thanks to the work of this project, on the morning of November 24th, 2021 a plaque was installed with the names and dates of death of the executed men and placed near the entrance of All Saints cemetery, Jesmond. The small ceremony was attended by Dr Shane McCorristine, Dr Patrick Low and a number of relatives of the executed.