“This morning…the blood of an unhappy criminal will have been shed…Happily such a spectacle, never exhibited except in cases of premeditated murder, is exceedingly rare in this town…We hope that Newcastle will be spared again from witnessing a Saturnalia of blood.”

— Newcastle Guardian

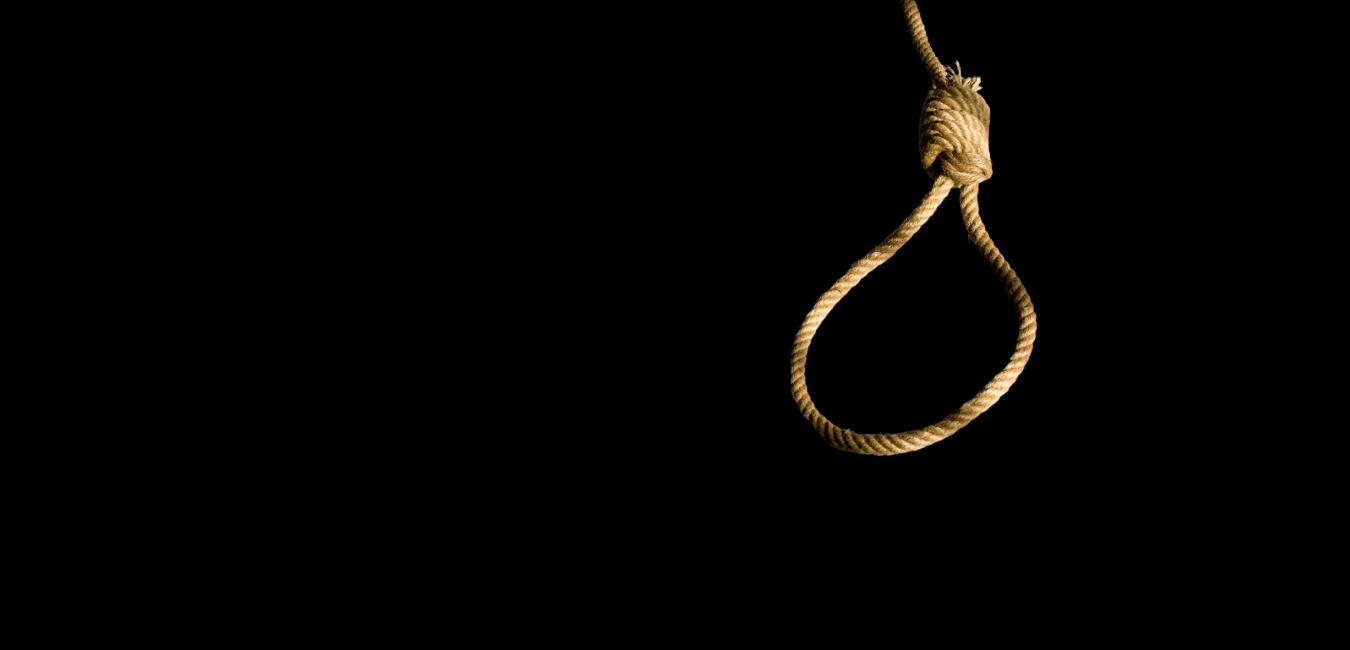

Executions

It may seem remarkable to the modern reader, but in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century executions took place in front of thousands of spectators in Newcastle. Indeed, for centuries prisoners guilty of a capital offence were executed on the Town Moor (open land to the North of the city). In almost all instances the punishment of death was to be hanged by the neck until dead – with beheading reserved for nobility. Although, not nearly as prolific in the North East as in London and the South of England, the hangman was not an entirely infrequent visitor to these parts. Between its opening in 1828 and closure in 1925 16 prisoners suffered the rope (15 male and 1 female) but only 14 took place on or within the walls of the prison itself. To find out why we must look at changes to execution in the nineteenth century.

During the lifetime of Newcastle Gaol, significant changes were made to execution that would both limit its use and significantly change its presentation. The first was a series of legal reforms in the 1820s and 30s that removed a vast number of crimes from being punishable by death. Where once over 200 crimes (of vastly differing magnitude) had been subject to the death penalty (known latterly as the ‘bloody code’), by the 1830s only a few of the most serious offences remained and, in reality, people were only hanged for murder from then on. The second and perhaps more fundamental change was the removal of execution from public view. The 1868 Capital Punishment Amendment Act (CPAA) legislated that from henceforth ‘judgement of death to be executed on any prisoner…..shall be carried into effect within the walls of the prison.’ What had once been a public spectacle, with reports of tens of thousands of people crowding on to Newcastle’s Town Moor to witness a convicted felon’s last moments, soon became an intensely private event.

Between its opening in 1828 and eventual closure in 1925, 16 prisoners of Newcastle gaol were executed (15 men and 1 woman) but only 14 of them were hanged at the gaol - Jane Jameson, (1829), and Mark Sherwood (1844), were both hanged on the Town Moor in Newcastle. Sherwood’s execution had been originally planned to take place on the exterior wall of the prison, but a large and fatal crowd crush at an execution in Nottingham (William Saville, August 1844) led to last minute adjustments and a change of location. Reporting on the decision the Newcastle Courant noted that,

“The sad occurrence which was lately witnessed at Nottingham…has caused the idea to be given up of carrying the sentence of the law into effect upon Sherwood in the immediate vicinity in the gaol, as it is feared some serious accident might happen (as at Nottingham) from the want of space to hold the vast multitudes who usually attend such occasions.”

““I cannot conceive anything more horrible than taking a man from prison, parading him through the streets up to the Town Moor, and then hanging him like a dog”

The eventual siting of Sherwood’s execution was on the Town Moor Race Course. The public nature of Mark Sherwood’s execution caused considerable debate on the Town Council in 1844 and ultimately led to future executions taking place outside the prison walls. Mr Alderman Donkin, opined “I cannot conceive anything more horrible than taking a man from prison, parading him through the streets up to the Town Moor, and then hanging him like a dog (hear, hear). Moral Effect! Why more picking of pockets takes place at the foot of the gallows than anywhere else in ten times as many days or weeks in the year.”

Newcastle moved comparatively late to extramural executions (outside or on the prison walls). By comparison, in London, execution moved from the open land of Tyburn to the external walls of Newgate prison in 1783 and in nearby Durham the first extramural execution at the prison took place in 1816. By comparison, the first execution to take place at Newcastle prison was not until 1850. The first victim of these newly relocated gallows was a man called Patrick Forbes. Forbes was an Irish Labourer and had been charged with the murder of his wife, Elizabeth Forbes. Much debate ensued about where the execution was to take place, with the eventual decision that a gallows would be erected against the exterior North Wall of the prison. In a rather astonishing move the decision was made to make a hole in the prison wall from which the prisoner would emerge. Fears of an unpredictable crowd meant that this was deemed safer than processing the prisoner from the gates to the gallows. With Forbes’ execution set for Saturday 24th August, stonemasons arrived on the Thursday prior. The authorities were right to be fearful as numerous reports of the execution estimated the crowd on the day at about 20,000. The Newcastle Journal noted

“the composition of this crowd will be perfectly well understood by newspaper readers. Vast numbers were of that class which, in all large towns, delight in ‘the horrible,’ many were females of doubtful character, and not a few were recognised by the police as notorious pickpockets who doubtless plied their vocation as well as they could. Of course, no salutary impression, but the very reverse, could be produced on such parties by witnessing an exhibition so brutal and revolting.”

But not everyone was behind the practice of hanging, indeed numerous newspapers, most notably the abolitionist Newcastle Guardian, stated,

“This morning…the blood of an unhappy criminal will have been shed…Happily such a spectacle, never exhibited except in cases of premeditated murder, is exceedingly rare in this town…We hope that Newcastle will be spared again from witnessing a Saturnalia of blood.”

The last execution to take place in public view was that of George Vass in March 1863. Vass, 19, was charged with the murder of Margaret Docherty. Unlike at the execution of Forbes, the authorities made the decision to remove Vass entirely from interacting with the crowd and set the execution on the prison roof. Although still technically visible, in reality, to most of the gathered public it would have been as close to a private execution as they would experience. One newspaper reported that ‘nothing is visible from the street but the beam of the scaffold.’

In the interim between Vass and the next execution (John William Anderson 1875) hanging had been moved to behind the prison wall. From then on all executions took place out of public sight. The only indications that the grim task had been undertaken was a posted notice on the external walls of the prison, confirming as much, and the raising of a black flag above the prison walls (even the flag was eventually removed by the Home Office in 1902). Between 1868 and the eventual closure of the prison 12 prisoners were hanged inside the prison, all of them male.

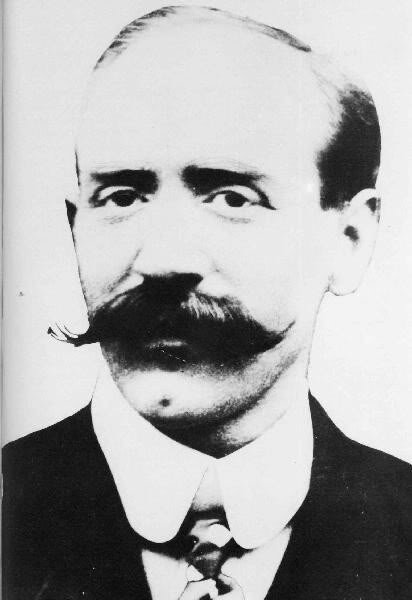

Some of the cases attracted national attention and were even the subject of radio plays. Arguably, most notable amongst these was the case and eventual execution of John Dickman in 1910. Dickman had been charged with the murder of John Innes Nisbet, on a train travelling between Newcastle and Alnmouth station on the 18th March, 1910. Nisbet was carrying the wages for a local colliery at the time and his body was found under a seat in one of the train carriages. The murder caused great consternation and to this day is still the subject of numerous reinvestigations, including on BBC’s Murder, Mystery and My Family. It also featured as a case on The Black Museum radio show, narrated by Orson Welles (available below).

The last executions at Newcastle Gaol took place on the morning of 26th November, 1919. Ernest Scott and, shortly after, Ambrose Quinn were both hanged for murder (Scott for the murder of his sweetheart and Quinn for the murder of his wife). As in all cases of execution at the prison their bodies were buried within the prison walls and, as part of the punishment, denied a Christian burial. The location of these bodies was to become a major concern of the governing authorities when the prison was closed for demolition in 1925. To find out why, visit our burials page.

The Final Prison Executions.

Ernest Bernard Scott & Ambrose Quinn

Execution Timeline