Prison History

Closure 1925-present

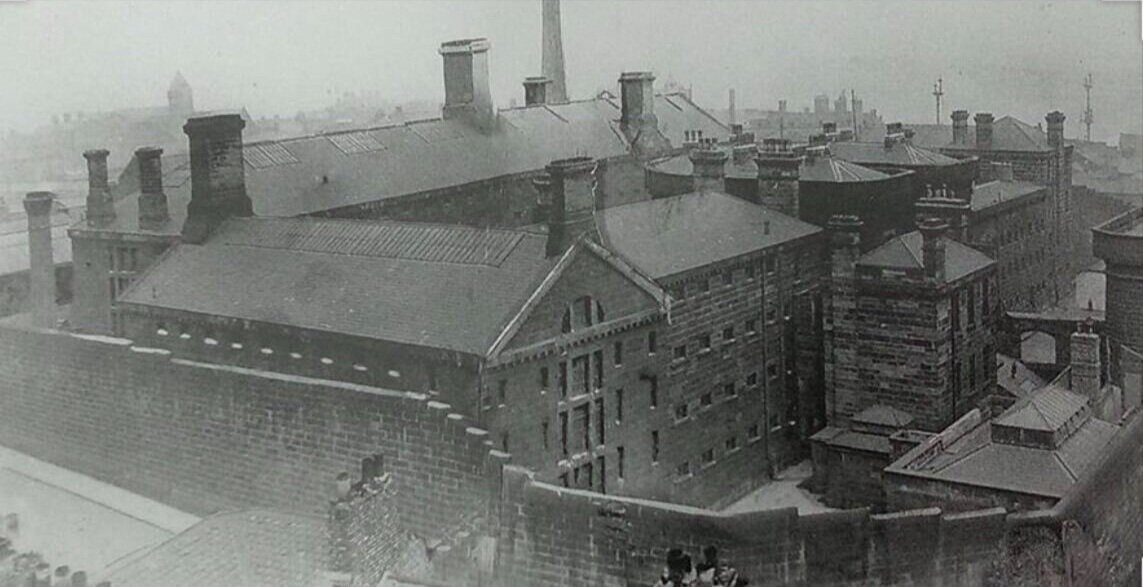

In September 1925 a local newspaper reported that a group of “keen faced business men” were taking stock of old Newcastle Gaol, trying to estimate the cost of removing this “gloomy pile”.

“The men who designed and built the gaol must have been people of great thoroughness. It is built as though it were meant to withstand a siege, and in the strength and grimness of its aspect it cannot have failed to exercise an awe-inspiring effect upon successive generations. We live in an age when such elaborate apparatus against violence and crime is not necessary. The gaol had become an anachronism in the midst of a well-behaved and peaceable city…and so its career has been terminated.”

Newcastle Gaol was one of many regional prisons closed by the Home Office after 1914, reflecting a dramatic national decrease in prisoner committals and an increase in alternative spaces of incarceration (e.g., Bortsals and reformatories).

The gaol may have closed but it left behind some unfinished business. Although it was primarily a space of incarceration throughout its history, for some it was a place of burial. 15 men and 1 woman were executed by hanging in Newcastle between 1829 and 1919, most of them dying in the execution shed located on the grounds of the prison. By law they were denied Christian burial as a further punishment and their bodies were buried within the walls of Newcastle Gaol. The hangings of Ernest Bernard Scott and Ambrose Quinn on 26th November 1919 were the last executions in Newcastle and on 31 March 1925 the gaol was closed by the Home Office. It was demolished soon after but only 12 bodies were found in the prison yard. These were interred in secrecy and without ceremony in an unmarked plot in All Saints Cemetery, Jesmond, on the morning of 15th October 1925.

Resurrectionists or Reburial?

Discover the secret of the missing bodies of the executed

Meanwhile, a public auction was held in the exercise yard and over 800 lots were sold, including the semi-circular chapel, two organs, and a Roman Catholic altar. Newspapers reported that “women visitors” bought up domestic and kitchen articles while others purchased spoons “once used for the ‘forcible-feeding’ of obstreperous prisoners”. When the gaol was demolished some of the stones taken from the walls ended up supporting the foundations of the Tyne Bridge, then under construction. Some of the good quality stone was also used in the building of St James’ and St Basil’s Church in Fenham around the same time.

One of the main problems the gaol faced from its inception was the relentless urban development around it. At 1.8 acres, the gaol site was smaller than a football pitch and amid the busy pubs and tenements surrounding Carliol Square was Erick Street, Newcastle’s red-light district in the nineteenth century. Meanwhile, from as early as the 1830s the district of Manors was earmarked as a potential railway hub and in 1836 the builder and planner Richard Grainger proposed a railway line from North Shields to Newcastle that would run just alongside the gaol, rather than arriving into the centre via Quayside or Pilgrim Street. In the 1840s John Dobson designed some of the local railway infrastructure and his Manors station building was just over 50 metres south east of the gaol walls. Alongside the noise of passenger trains and passing freight, the prisoners would have been disturbed by the “pandemonium” of the Carliol Fair every year. They would have also heard children playing from the Dobson-designed Clergy Jubilee School a mere eight metres from the walls, and indeed schoolchildren would frequently shout at the inmates and vice versa. By the mid 1920s city authorities were planning new north/south thoroughfares made possible by the Tyne Bridge project. With a new road planned connecting City Road and Barras Bridge, the gaol stuck out like a sore thumb in a district already busy with manufacturing and transport infrastructure right on its doorstep.

The closure of the gaol in 1925 coincided with yet another regeneration of the district east of Pilgrim Street. Despite spending enormous sums of money on the gaol since 1822, the Council decided to purchase the site from the Home Office and, although other projects were mooted, Telephone House was built there to house the Newcastle Telephone Exchange. In 1927 Carliol House opened on the corner of Pilgrim Street and Market Street. This Art Deco-inspired structure was purpose built to house the North Eastern Electricity Supply Company. A few years later the new Central Police and Fire Station opened opposite Carliol House, creating grand, modernist statements about Pilgrim Street - what one newspaper called “Newcastle’s front door”. Despite the building boom of the 1920s, the East Pilgrim Street district became dominated by swathes of road construction associated with the Swan House roundabout and Central Motorway projects in the 1960s/70s. In this brutalist future of motorways, car parks, and walkways in the sky, older buildings like the Holy Jesus Hospital and All Saints Church now seemed anachronistic and out of place, with the centuries of foot traffic from Pilgrim Street to Quayside a distant memory.

Important research on the history of the gaol was carried out in the 1990s by the late Barry Redfern, former Chief Superintendent of Northumbria Police. However, outside of holdings in local libraries and archives, few signs of the Gaol’s existence or the city’s places of execution remain. However, the East Pilgrim Street area has again been earmarked for regeneration (see East Pilgrim Street Development Framework, 2016) and a cultural/heritage component of this development will be crucial in sharing the tangible and intangible heritage of this area to new generations. This website is the opening phase in a long-term project to gather together research, ideas, memories, images and any creative content that can help tell stories about Carliol Square, crime and punishment in Newcastle, and more broadly, the East Pilgrim Street area and its history.

Since the construction of Telephone House on the site of the gaol the occupants of these buildings have been many and varied. The building served as a telephone exchange for several decades before other tenants moved in, including a coffee shop, dance studios, tattoo parlour, and the World Headquarters nightclub. Aerial views of Carliol Square indicate that the footprint of the Gaol can still be detected in the size and scale of Telephone House. This, along with the memories and stories associated with the site remind us that the ghosts of Newcastle Gaol can still haunt passers-by as we approach 100 years since its closure.

Timeline