A Long-Buried Secret

I have known what it is to witness the bones of a friend, not in the grave half so long as the period just specified, tossed up to the surface to make room for another.”

- Rev R. Pengilly’s address to the assembled at the first interment of Westgate Hill Cemetery –

Newcastle Courant 24th October, 1829 p.2

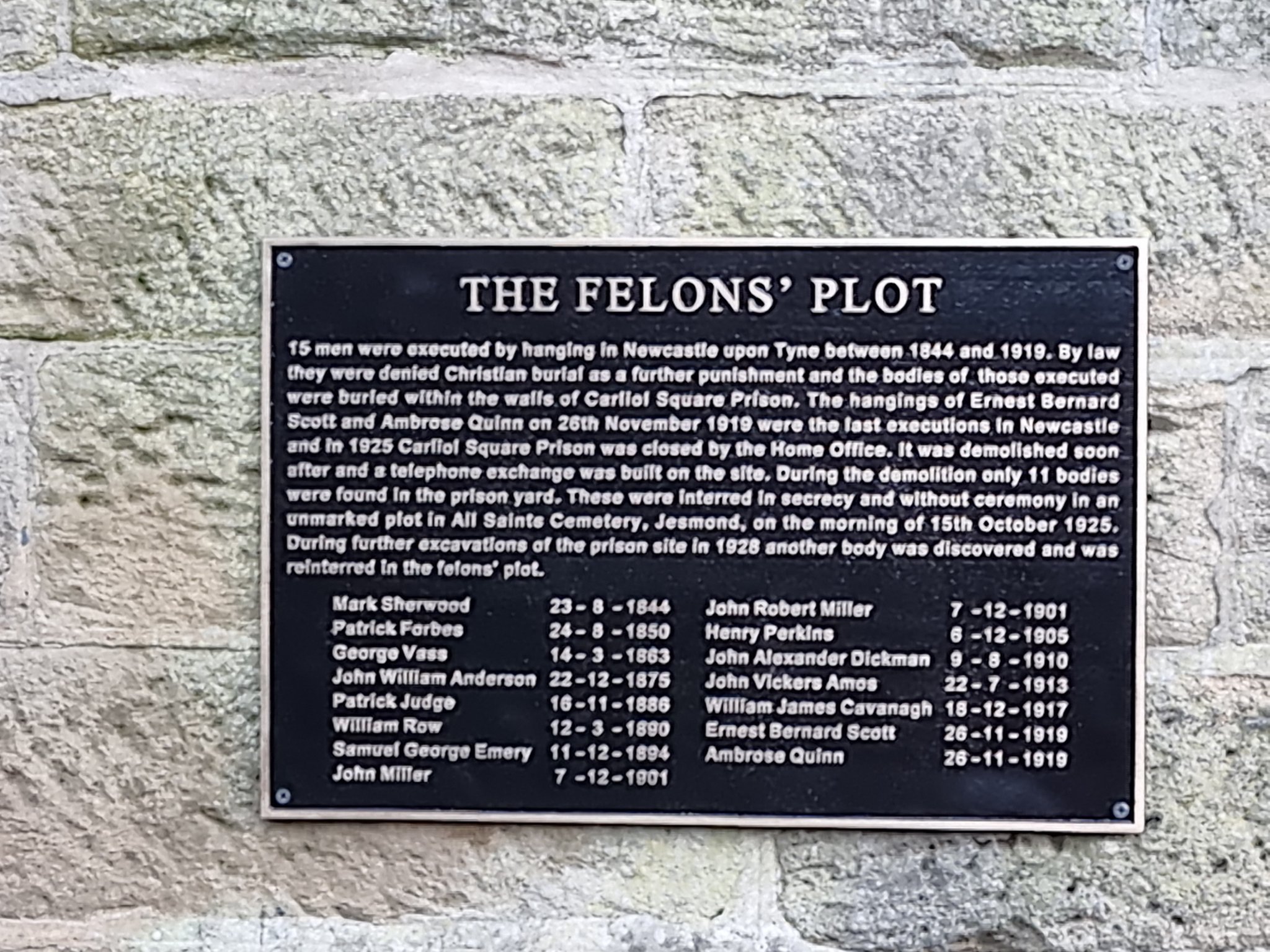

During the project to discover the gaol’s lost history, one of the most intriguing mysteries was the final resting place of the bodies of the executed men and women. Through my own PhD research, I had managed to account for 15 of the 16 people executed in the lifetime of the gaol, establishing that they had all been buried within the precincts of the gaol. Their burial sites had been crudely marked on nearby wall stones (until an HO Memorandum declared even that to be unacceptable and from henceforth the only record was an official map sent to the Home Office). However, when studying the burials one of the first exciting finds I made was that not all the bodies were accounted for when the exhumations were undertaken. Of the fifteen recorded burials only 12 bodies were found, a thirteenth empty coffin was found and 2 others were presumed missing.

Thanks to assistance from the public on this project we found that one of the missing bodies was discovered during the demolition works but was never formally identified. So, we knew definitively that at least 13 of the fifteen bodies were recovered and reinterred in All Saints Cemetery, Jesmond, under cover of darkness. Of the remaining two that were never found we know that they were at least provisionally buried within the prison wall as the sites were marked and officially recorded. However, the final resting place of one prisoner, still eluded us. We could never find any record or official evidence for the burial provision and plot of the first person executed in the gaol’s lifetime (and also the final woman ever hanged in Newcastle) Jane Jamieson. Now, after years of endeavour, I can finally report that I know where she was buried and the answer was so simple, it was literally staring me in the face.

Jane, a fish hawker on Newcastle’s Quayside, was sentenced to death for the murder of her mother in 1829. She had run her through with a poker at her mother’s lodgings in the Keelmen’s Hospital (pictured below in 1885 and now). The crime gripped the public imagination (of which more here) and there were detailed reports of her case, trial and execution in the local papers and later local histories even noted a detailed breakdown of the cost of her execution. In all these reports though there was never any mention of what provision, if any, was made for her burial. Similarly, she was not named or recorded in the files sent by Newcastle Gaol to the Home Office.

One of the reasons that Jane’s burial may have gone unrecorded was that her execution fell at a time (1829) when post-mortem punishments were still attached to the crime of murder (a provision of the 1752 Murder Act). The two legislative options available were for a prisoner to be Gibbeted (Hung in an iron cage from a tall wooden post) or public dissection, a procedure undertaken by the Barber Surgeons (pictured below) and often available to view by a paying public. In addition, the refusal of a Christian burial was an intrinsic part of the post-mortem sentence – the Murder Act stating that “in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried.” However, through my studies, most notably at executions in Durham, there was some evidence of localised discretionary provisions made to the families of the condemned and it was not uncommon for the body to be handed back to the family of the deceased. Also, it was not uncommon for the Barber Surgeons to gift each other the bones of the deceased (a macabre relic, if ever there was one).

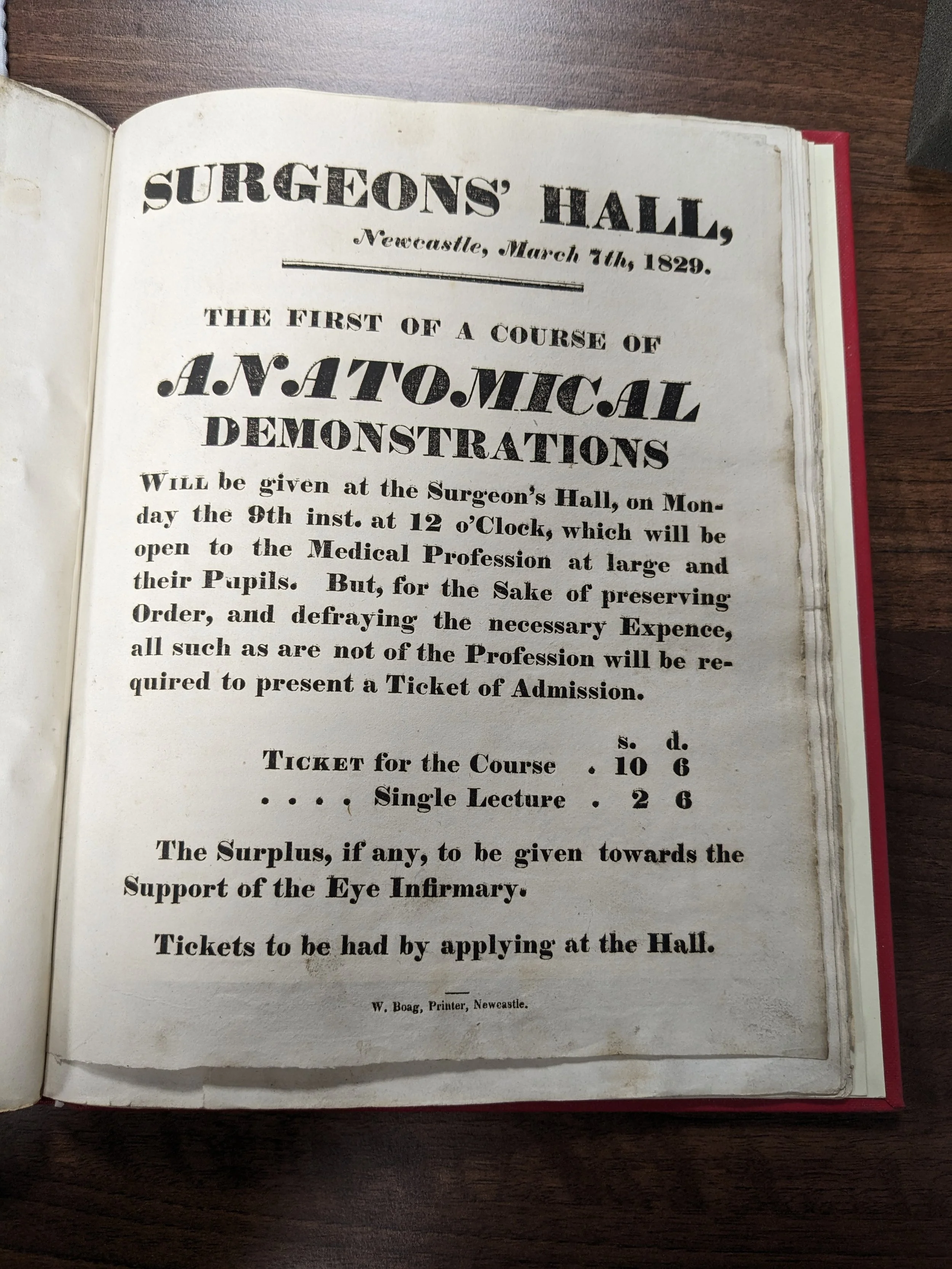

Recent research has shown that gibbeting was an exclusively male punishment – as such Jane was sentenced to dissection by the Barber Surgeons. The newspapers at the time and later histories of the region, carried detailed records of the dissection itself (undertaken by Surgeon John Fife, later Town Mayor), but there was never any report of the burial. Sadly, the trail ran cold there with the extant newspapers not recording any detail that may help us answer this mystery. That is until two weeks ago, when I stumbled upon an ephemera collection (John Bell’s) in the library of Newcastle University.

Advertisement for the dissection of Jane Jamieson’s body. John Bell Collection, Newcastle University.

John Bell, born in 1783, was a land surveyor, bookseller, and noted antiquarian who lived in Newcastle at the time of Jane’s death. Newcastle University holds a remarkable collection of his papers from the time and amongst them is a detailed record of the crime, trial and execution of Jane Jamieson – something he had taken a keen interest in. He even wrote to the leading Barber Surgeon, John Fife, who undertook the dissection and anatomical lectures on Jane’s body, asking of him if it would be possible to “beg the favour of any particulars which may transpire and which might be communicated to one of the unlearned.” Fife had previous for divulging the details of a dissection, Bell himself recorded that he was, “so good as to favour me with a slight account of the dissection of the body of Charles Smith in 1817.” As if this treasure trove of information was not enough for one day’s find, imagine my surprise when on the very last page I came across this handwritten note, copied from the Newcastle Chronicle, March 28th, 1829.

“Jane Jameson – The Remains of this unfortunate woman were interred in the Ballast Hills Ground in the afternoon of Friday Sen’night, the last of the anatomical demonstrations having been concluded on the preceding day.”

So, there it was, right in front of me! Jane’s body lies in Ballast Hills Burial Ground! This was particularly amazing to me as I have walked on Ballast Hills, accompanied by my scruffy lurcher, on an almost daily basis for years. I always loved trying to decipher the names and details of the broken gravestones that make up its pathways. I suppose a small part of me was always hoping to discover something that might offer us a clue or throw up more fascinating stories, but I never thought it would help us find Jane.

Ballast Hills Nov 20th. Author’s own image

Broken gravestones that now form the path at Ballast Hills. Author’s own image

Remy The Lurcher/Assistant Researcher at Ballast Hills. Author’s Own Image.

The parlous state of burial grounds in the North East was much attested to in the early 1800s, but perhaps worst of all was the state of Ballast Hills, a longstanding Dissenters Burial Ground (for people of a non-established/non-conformist religion) in the Ouseburn to the East of Newcastle. Established as a cemetery for non-conformists it was also popular with the region’s poor, owing to the comparatively minor burial fee of sixpence. Despite its diminutive size, it soon became one of the largest Dissenters’ burial grounds outside of London. In 1824, 805 of the 1454 burials that took place in Newcastle were at Ballast Hills. In this sense ‘over half the citizens of Newcastle were…denied ‘the civil advantages of burial’ afforded to Anglicans. A member of the Dissenter community, who had been privy to initial meetings to establish a new site, burnished the Newcastle Courant with the figures for recent internments at Ballast hills. The letter’s author opined that they had buried more people than in all the other churchyards in Newcastle combined, “Ballast Hills have received, in only six years, above three thousand six hundred bodies! Where, without disturbing these, can room be found for another six years?” It was later replaced by the Westgate Hill Cemetery and the sermon given by the presiding Reverend Pengilly was very instructive of how bad the situation at Ballast Hills had become.

“Everyone who has paid any considerable attention to the former places of interment, whether in reference to the church yards or the burial place at the Ballast Hills, must know, that except in the very small recent enlargements, the portions of the ground so appropriated have been literally crowded with the dead…I have known what it is to witness the bones of a friend, not in the grave half so long as the period just specified, tossed up to the surface to make room for another.”

Ballast Hills Cemetery, 1926, courtesy of http://www.tynesidesilentcities.com

So, Although Jane’s final resting place was perhaps not a happy one, it is remarkable that she was afforded one. In doing so, the authorities at the time showed discretion above the provision of the law. What is perhaps less remarkable is the final line in Bell’s hand-cribbed note.

“A Great number of persons assembled to witness the interment.”

The fascination surrounding the case would undoubtedly have drawn large crowds to the burial. Indeed, the fear around the public interest towards capitally condemned felons was one of the reasons that the punishment of prison burial replaced the post-mortem punishments of Dissection (1832) and gibbeting (1834). The authorities were increasingly keen to remove the prisoner’s body from public view to avoid any possibility of martyrdom.

Jane now has another remarkable thing to add to her dubious legacy. Not only was she the first and last woman to be hanged at Newcastle Gaol, she was the only capitally convicted felon to have been buried outside its walls.

I hope we can now get her final resting place marked in the same way that we managed to with the other prisoners who were reinterred, in an unmarked location and under the cover of darkness, at All Saints Cemetery Jesmond.