Prison History

Operation 1828-1925

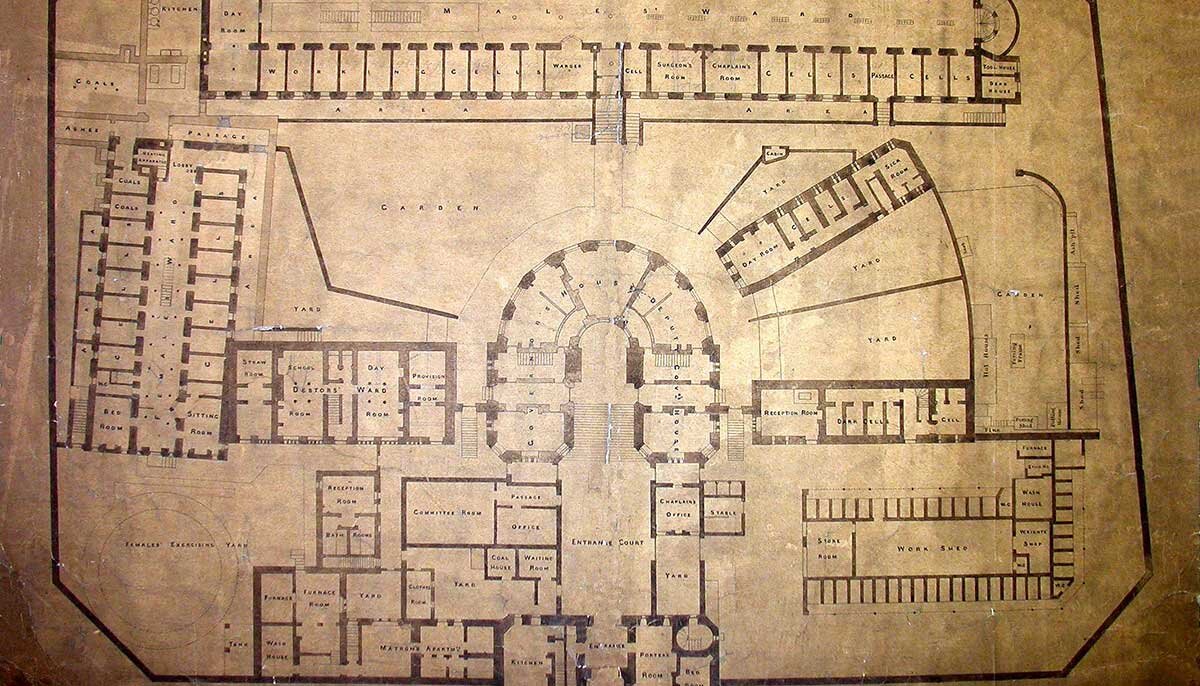

Newcastle Gaol opened in 1828 to great optimism and confidence. It was hoped that the horrors of Newgate were in the past and that prisoners could now receive adequate means to work and receive instruction in a well-managed situation, and thereby reform themselves. Yet by 1838, when regular inspections of prisons commenced, the gaol was condemned as unsuitable, damp, overcrowded, and lacking in real pathways to reformation. Prison reports indicate that cells were just 8 feet by 8 feet and most rooms were unheated. Furthermore, Town Council minutes indicate that from 1836 there was a gradual laxity in prison discipline with alcohol circulating and regular fights taking place.

In a gaol Dobson had designed for around 100 prisoners there were 176 prisoners incarcerated at one stage in 1836. Already there had been several escapes and an ingenious plot to make a set of keys from lead taken from the water-closets. The inspector complained that prisoners seemed to spend as much as 16 hours a day in bed during the winter months and the chief employment for the men was breaking stones and treading water outdoors. Compounding the problems were the presence of debtors in the gaol, who were incarcerated under different conditions than other offenders. Debtors could have visitors for three hours per day and receive three pints of ale. This they used to sell on to other prisoners, as well as the tobacco they smuggled in.

The prison inspector continued to condemn Newcastle Gaol in his reports in the 1840s, recommending a complete rebuild, reform of labour projects, and the sacking of some staff. In his 1841 report he complained about the “gruffness” of some of the officers in their dealings with prisoners, but he was informed “that a harsh mode of speech is common in this district, and that it does not indicate unkind feelings”. Another persistent criticism was that there was no proper classification system to manage the prisoners. It was only in 1840 that boys began to be separated from the men, and the prison inspector noted that many of these boys were committed for petty thefts on the Quayside, such as the theft of old rope and scrap iron.

The number of arrests for this type of petty theft increased because of the establishment of the River Tyne police in 1845, but the Newcastle Borough police were also expanding in numbers and remit, contributing to more arrests and committals. Police force numbers rose steadily from 164 in 1869 to 200 in 1875 and almost 300 in 1890. This rise in policing was matched by increases in the daily average of inmate numbers, from 94 in 1838 to 182 in 1863 to 301 in 1909. As a newspaper put it in 1859: “The town of Newcastle-upon-Tyne has become known for two things - the impossibility of a thief for any great length of time to evade the lynx-eye of the police within its boundaries; and the incapacity of our prison officials to keep our prisoners”.

In 1846 there were 99 prisoners present on the day of inspection, and of this 14 were Scots, and 19 were Irish, reflecting the mixed roots of people in Newcastle. Of the 750 prisoners entering and leaving the gaol in 1846, only four were found to be able to read and write and this reflects some shocking statistics gathered at the time which indicated that out of a population of 51,000 in Newcastle, nearly 8,000 were children between the ages of 5 and 15 who were not in education. Sandgate was considered the most impoverished district and many of the child prisoners in the gaol - especially the Irish - were from there.

An excoriating letter from the chaplain John Irwin in 1858 laid bare some of the long-term failings of the gaol. It was, said Irwin, a “paradise of thieves”, a “nest of villainy”, “a hot-bed of vice”, and a “house of corruption”. There was no proper heating or lighting; there were no proper labour tasks; and prisoners communicated with each other in contravention of the rules. Prisoners were found all huddled together, “each corrupting the other”. The gaol had become, it seems, another Newgate, and Irwin was concerned that there was no reformation possible in the prison.

“What right have we, because a young girl commits a brawl in the streets, and is too poor to pay the fine, or sells oranges on the footpath, or steals her mistress’s lace collar - her first offence - to shut her up, bolted and barred and locked in night and day with the vilest, the most hardened, the most abandoned of her sex - women from whose contact she would have shrunk with a shudder had she met them in the street.”

“A paradise of thieves…a nest of villainy, a hot-bed of vice and a house of corruption”

Prison Chaplain - John Irwin

The punishments for disobedience and disorder in the gaol were usually solitary confinement in the “dark cells” or a reduction in diet. On some occasions prisoners were flogged with the cat o’ nine tails as part of their sentence, and when this took place the Mayor, councillors, and the gaol surgeon would attend.

J.T.H. Hoyle, Newcastle’s coroner from 1857-85 was a frequent visitor to the gaol, dealing with inquests into the sudden deaths of prisoners, the infant children of female prisoners, and cases of suicide. Suicide was a common occurrence in the Gaol throughout its history and the most common way prisoners killed themselves was by tying some oakum rope to the ventilator shaft above the door and hanging themselves. In March 1882 a 13 year old boy named Henry Maughan hung himself from the bell handle with a towel. He had been convicted of stealing a duck and was sent to gaol for ten days to be followed by four years in a reformatory.

So what went wrong with the Gaol that had inspired such optimism? Certainly there was an increase in prison detentions associated with a growth in professional policing and the reduction of transportation as an option for judges in the mid century. Another major issue was that the gaol was still incarcerating debtors, which impacted on available space for criminal offenders - it wasn’t until 1869 that any serious reform of debt legislation was passed. Fundamentally, however, the issues the gaol were facing were down to the fact that this was a city centre prison responding to an increase in population, an increase in policing and punishment of urban, poverty-related crime, and the relentless growth and development of a city around its very walls.

“The town of Newcastle-upon-Tyne has become known for two things - the impossibility of a thief for any great length of time to evade the lynx-eye of the police within its boundaries; and the incapacity of our prison officials to keep our prisoners”

In 1857 four prisoners on remand for garrotte robberies escaped from the gaol due to the incompetence of the turnkeys who left several cells unlocked at night. Apparently 16 prisoners were able to leave their cell, but only four “desperate characters” were “game” enough to scale the walls. They did this placing a long plank against the inner wall near the work yard and then using a rope made by tying their bed rugs together. As the walls were 25 feet high, they were worried about the drop and one of the men, Hays, dislocated his ankle on landing. As he could not walk, his confederates dragged him to an arch close by and “pulled the ankle right again”. The men kept moving in the direction of Arthur’s Hill and two of them eventually made their way to Carlisle where they were arrested, miserable-looking and barefoot, by Mr. Sabbage, Chief Constable of Newcastle.

In 1858 another garrotte robber, Robert Boyd aged 22, escaped from his cell by making a hole in the roof with a chisel. Using a bed rug rope he lowered himself onto the galleries and gained access to the work yard. Remarkably, there were still long planks lying around and he used it to scale the wall. Once there he placed some bags of teased oakum over the spikes and used his rope to descend. Boyd was on the run for 3 weeks before recapture. In 1859 a gang of thieves nearing the end of their sentence also managed to escape, and these were an interesting crew. Led by the wonderfully-named Joseph Preshious and Walter Scott Douglas, they were daring jewellery thieves who preyed on businesses near Pilgrim Street and the Royal Arcade. They had apparently been trained as joiners and were able to bore holes in secure doors using professional tools. Douglas had been transported before and apparently learned some languages; he once taunted a policeman with some papers written in Latin. When the gang escaped, probably using the same methods as their predecessors, Preshious injured his ankle on the drop and was apprehended by Sabbage - he was later sentenced to 20 years for his role in the robberies.

Douglas went on the run until April 1860 when he was arrested in a pub on the Scotswood Road. On this occasion he was captured by Inspector John Elliott (Image: picture of Elliott), aka “Clencher”, who went on to become the Chief Constable of Gateshead. When nabbed, Douglas was found to have two loaded pistols in his jacket, as well as a set of false whiskers and stolen jewellery. A newspaper reported: “His appearance was fashionable in the extreme, and, to a less experienced eye than that our of our detective officers, might have passed for a highly-respectable man”. Douglas confessed that he was led into crime by his reading of the exploits of Jack Sheppard while in prison and that his escapes were emulating his hero. Douglas was brought back to gaol but remarkably after only a few weeks he escaped again. This time he used the distraction caused by divine service on a Sunday to get out into the prison grounds where he built a scaffold using tables and benches and reached the top of the eastern wall. It was believed he then used a pole left by masons working on the Dobson designs to fix it against the Jubilee School opposite, and then descend from this using a bed rope. “The mistress of the Church Jubilee School on the opposite side of the lane…saw him descending in this manner, and the mistress called out to him, to which he replied only by an oath”. Douglas made for New Bridge Street and Pandon Dean and escaped the clutches of the police once more.

However, Douglas seemed to enjoy the chase and had a habit of writing poison pen letters to the police and his victims. A few days after his escape he sent one such letter to the Deputy Governor of the gaol in which he expressed a determination never to return to Newcastle again, adding a hope that the prison officers would not be blamed for his escape. He also hinted that he had a “small account” to settle with one of the detectives, for which he was prepared at any time. This was clearly a challenge for Elliott and Sabbage who eventually tracked him down in 1861 to Whitecapel in London, where he was arrested, under an alias, for burglary. “Ah! How are you Mr Sabbage! Ah! Mr. Elliott, I suppose you have come to prove my conviction”. Despite finding Douglas, Elliott was unable to get him remanded back to Newcastle Gaol because while in Coldbath Fields Prison he stabbed a warder with an iron spoon that had been sharpened.

Despite the deficiencies in the site of the gaol and the overcrowding and expense associated with it, the building somehow survived closure into the twentieth century. Another shift was to come in 1877 when the Gaol passed out of the control of the Town Council into the hands of the Prison Commissioners, who renamed it H.M.P. Newcastle. Despite the new name, ever increasing numbers of inmates - reaching annual average figures of over 5000 by the 1890s - highlighted the persistent problems about the site of the prison, the conditions and state of the buildings, and the difficulties in reforming repeat offenders. In 1895 the prison commissioner Colonel Michael Clare Garsia summed up the feelings of many when he told a Parliamentary Committee meeting that “Newcastle is the worst prison you have got”. Although plans to demolish the prison were then afoot according to Garsia, it would take another 30 years for the Home Office to close the prison and transfer the inmates to Durham.

Timeline