“If we had to describe a ‘typical’ prisoner in Newcastle Gaol it would be a young working-class man in his 20s who worked as a labourer, was born in Northumberland, and was convicted of larceny.”

Daily Life

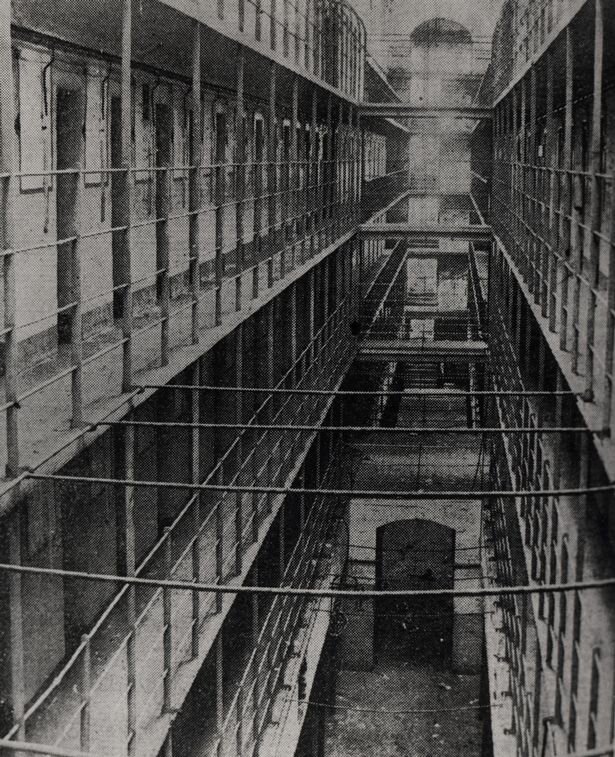

To begin to paint a picture of life in Newcastle Gaol we must recognise the impoverished conditions that most people lived in during the nineteenth century. The Gaol emerged from Newcastle and was a part of its evolution: it represented the modernism and large-scale ambitions of the town and its authorities, but also the destitution, violence, and despair of many of its inhabitants. There were many roads to imprisonment, but once inside the imposing tower gate of the Gaol on Carliol Square, life adopted familiar patterns and routines.

We can be sure, given the poverty levels and rates of illiteracy for most of the nineteenth century, that social conditions were a factor in the causes of crime and the parameters of criminal justice. If we had to describe a “typical” prisoner in Newcastle Gaol it would be a young working-class man in his 20s who worked as a labourer, was born in Northumberland, and was convicted of larceny. Newcastle had a relatively low rate of capital punishment, and despite housing many serious offenders, the gaol was not known for its notorious inhabitants. Political and military prisoners were a rarity in the gaol, although it did host Suffragettes in 1909, German internees during World War 1, and Sinn Féin activists during the Irish War of Independence. For most inmates, sentences were usually short - a number of months of hard labour - unless the case had come through the Assizes. Of course, these generalisations do disguise the diversity of inmates (men, women, and children), their offences, nationalities, and prison experiences.

Prisoners spent most of the duration of their sentence inside their cells, apart from short periods spent exercising, working in the stone-yard, garden, or kitchen, and attending religious service on Sundays. The Gaol segregated male and female prisoners into different wings and yards, and women had a separate staff of matrons and wardresses to attend to them. Prison inspectorate reports and criminal statistics are fascinating, but when researching the history of a gaol it is hard to avoid the fact that most primary sources come from one side only, from magistrates, judges, journalists, and police. But some prisoner perspectives have survived and one such rich source was written by an inmate in 1879 giving us an insight into what life was like on the inside.

The author describes how, after being sentenced to 6 months hard labour in Pilgrim Street Police Court he was led handcuffed the short distance to the gaol with other male Assizes prisoners. A “sympathising mob” followed them, chiefly composed of “small boys, unbonneted women, and ‘roughs’ from the odoriferous locality - the Stockbridge”. Once past the massive door of the Gaol the new arrivals entered a reception room where they stripped and had a brief bath. They were introduced to the rules - strict silence; no communication with other prisoners; no bartering of provisions; work hard. The men were examined for distinguishing marks, were measured and then given their clothing. A jacket, waistcoat, under-garments, stockings, and dirty brown trousers which seemed to be half corduroy and half canvas. These had a yellow and white stripe running down them and were monogrammed “N. G”.

The author was brought to his cell, which was 14 foot by 10 foot, and shown his plank bed and three rugs. There was a wash basin, table, stool, tap with cold water, and bell for the warder. The day began at 5:45 am with wake up and breakfast served on a tin pannikin slid through the door. At 6am prisoners were given their day’s work - 4lbs of oakum to be teased out - a tedious and monotonous job. Female prisoners would sometimes be given needlework as an alternative. If inmates managed their day’s work they were liable for a slightly better diet and a promotion to a hammock bed. This was hard labour and continued, with some short interruptions, until 7.30pm, Monday to Friday. On Saturday the prisoner cleaned his cell, himself, and was given a change of under-garments. Services on Sunday were a chance to surreptitiously communicate with other prisoners, as was activity in the exercise yard afterwards. Shaving was abolished, although some men managed to shave with sharpened knives. Tobacco, or ‘snout’ was the great want and all newcomers were begged for a bit. Talking between cells was possible if prisoners bored holes using the wire rim of a dinner tin, but they were only allowed one visitor every three months. Despite these hardships, the author of the reminiscences believed the system was orderly, temperate, and capable of inspiring reformations of character.

Among the prisoners incarcerated for property offences and law breaking were debtors imprisoned for owing money. They had their own ward and were imprisoned under different conditions than the rest. A drawing by G.B. Richardson (pictured below) indicates the relative comfort they lived in: a proper bed, fireplace, and no less than three windows. However when John Kincaid inspected the gaol in 1850 he found an old man of 81 years who had been in prison six years and had become “stone-blind”. Debtors could have visitors for three hours per day and receive three pints of ale. This they used to sell on to the other prisoners, as well as the tobacco they smuggled in.

“To collar at breakfast or supper an extra drop of ‘skilly’ (gruel) is considered a masterpiece of strategy.”

- Extract from A Prisoner’s Life at Newcastle Gaol (1879).

As the account above demonstrates, work dominated the daily life of prisoners. For most of nineteenth century, the main occupation for prisoners in Newcastle Gaol was oakum teasing. This punishment task involved picking out fibres from old rope for recycling into other products. It was repetitive and painful work with no variety or skills to make it interesting. By the 1890s the kind of labour carried out in the Gaol had diversified as a result of government contracts, and instead of repetitively breaking stones or teasing oakum as described in “A Prisoners’ Life”, prisoners were now ordered to make hammocks and life buoys for the Admiralty, mail-bags for the General Post Office, and to chop wood to provide the military with stores of kindling. Flax picking and picking out cotton waste replaced oakum teasing as the drudge work. These hours of work were punctuated by meal breaks, and food in Newcastle Gaol was simple and dull. Gruel, soup, and bread formed the staples of the prisoners diet, while cooked meat was occasionally served depending on the dietary class of prisoner. Women and boys under the age of 14 were served less than the men.

The “classification” system which underpinned Dobson’s original design was intended to separate prisoners and keep them in single cells, however overcrowding in the Gaol meant that inmates and staff mixed and interacted more than the authorities wanted. Indeed, barely 10 years after its opening, the Gaol was condemned by the prison inspector as damp, unsuitable, and lacking in real pathways to reformation. With the majority of the prison population being young men, violence among prisoners was also a problem in these early decades. An excoriating letter from the chaplain John Irwin in 1858 laid bare some of the long-term failings of the gaol. It was, said Irwin, a “paradise of thieves”, a “nest of villainy”, “a hot-bed of vice”, and a “house of corruption”. There was no proper heating or lighting; there were no proper labour tasks; and prisoners communicated with each other in contravention of the rules. Prisoners were found all huddled together, “each corrupting the other”. The gaol had become, it seems, another Newgate, and Irwin was concerned that there was no reformation possible in the prison. Punishments from warders could be harsh, although reports indicate that staff at Newcastle had less recourse to flogging than other prisons, preferring to use the dark cells to punish disorder. Suicide was a not entirely uncommon occurrence in the gaol and the 1853 inspector’s report mentions in passing that a woman died in her cell after setting her clothes on fire.

The Gaol was also a home for the governor and deputy governor, and their respective families. So far from being an isolated and restricted institution, the gates of the Gaol would have been opened many times a day to allow in deliveries, cabs, visitors, prisoners, and inspectors. For officers working in the gaol, there was always a risk of assault at the hands of a prisoner. In May 1886 John Cunningham was charged with attempted murder after he struck a warder named Thomas Wallace several times over the head with a stone. In June 1887 it was reported that J. Graham, the deputy governor, was approached by a prisoner during exercise and violently assaulted, leaving him with severe injuries to his head and arm. The violence could even pass beyond the walls, as a few years later the chief warder of the gaol, Samuel Newton, was attacked by four men on Low Friar Street. One of the assailants, William Mackle, aged 23, struck him with a leather belt, the buckle of which cut his head. Mackle, who had served time in the gaol, was sentenced to six weeks hard labour and another return to the supervision of Chief Warder Newton.

In 1902 the Governor regretted to report an increase in the committals of boys under the age of 16, from 32 to 76. Half of these boys had been convicted of gambling while the remainder were charged with disorderly behaviour, including vagrancy, playing football in the streets, throwing snowballs, letting off fireworks, and one was jailed for cruelty to a pony. In all cases the sentences were short - typically three days - but the experience must have been disturbing given the crowded nature of the Gaol. We should also remember that many of the female prisoners served their sentences while looking after their infant children: the 1881 Census records that five out of 34 inmates had infants as young as two months in their cells. This must have been a difficult experience, although perhaps with the guarantee of food and the daily attentions of the gaol surgeon and chaplain, prisoners had more structure in their lives than what lay beyond the gates.

Given the high number of recidivist offenders in the Gaol a number of reforming initiatives were launched in later decades to try to provide education, training, and post-release guidance. A Discharged Prisoners Aid Society was formed in the 1880s while by the 1900s an active Visiting Committee to the Gaol had improved the state of the prison library and delivered regular lectures to the inmates. For instance, a report from 1908 indicated that a “lady visitor” named Mrs Bentham took an interest in the education of female prisoners and delivered addresses on “Fresh air”, “Health”, “Burns and Scalds”, “Care of children”, and “Try again”. In the same year juvenile male prisoners were lectured on “Courage” and “Manliness” by Col. Coulson J.P., and the Rev. Bernard East, vicar of nearby St. Ann’s Church, gave a lecture on the exploration of Antarctica. Various schoolmasters and schoolmistresses provided rudimentary instruction to prisoners during the history of the gaol.

By this time Newcastle had introduced a form of the new “Borstal system”, a reformist attempt to reduce the number of juveniles returning to prison by providing a strict rota of training, labour, and other activities while inside. In Newcastle all male juveniles with a sentence of under three months were given the Borstal treatment, a method described in positive terms by the chaplain of the time: “every capacity of the youthful offender is worked upon for his advantage - morally by a course of lectures on secular subjects periodically delivered by one and other officials and authorities; physically by daily drill and exercise, and generally by close observation and strict isolation from older offenders”. Although governors always assured prison inspectors that children and juveniles were isolated from the general population, concerns about offenders mixing that were raised in the 1820s were still being repeated in the 1920s.

Despite Dobson’s imposing boundary walls, escapes and attempted escapes were relatively common in Newcastle Gaol. The gaol campus contained a stable, sheds, and work yards with material, tools, and rope sometimes left lying around, and the semi-regular construction projects to expand the number of cells provided opportunities to get the means to escape. These escape plots reached a peak in the 1850s and 60s, a period under the governorship of Samuel Thompson who was labelled - perhaps unjustly - “lax” in matters of discipline. The most sensational of these breakouts were by the jewellery thief Walter Scott Douglas, who escaped twice between 1859-60, but another incident details the bravado of a desperate female prisoner and the modern means of identifying a fugitive.

This breakout occurred in 1870 when Mary O’Neil, aged 27, escaped soon after she was sentenced to seven years in prison following the theft of a purse containing 12 shillings in Clayton Street. When the sentence was pronounced in court she said: “Thank you; that’s not nice. It’ll do me good. I’ll come back as bad as ever”. She then became disruptive, crying “Murder!” in the court, and had to be removed swiftly in a cab to the cells. O’Neil’s cell was in the female ward on the north-west side of the gaol and she was soon able to break an iron bar off the window and climb onto the roof, which was nearly level with the boundary wall. She then fastened a piece of rope to the roof of the wash house, got over the boundary wall near the main gates, and descended the 25ft drop. This was an astonishing escape and there were suspicions that O’Neil had had confederates helping her in the gaol. In any case O’Neil managed to evade capture for six months until a detective named Boys noticed her in Liverpool and matched her to a photograph that had been circulated. After arresting her, Boys was able to confirm O’Neil’s identity by spotting the “marks on her arm” that had been recorded on her prison file. This use of the mugshot and detailed description of bodily markers signalled the arrival of a new era of capturing offenders by means of technology.

Another shift was to come in 1877 when the Gaol passed out of the control of the Town Council into the hands of the Prison Commissioners, who renamed it H.M.P. Newcastle. Despite the new name, ever increasing numbers of inmates - reaching annual average figures of over 5000 by the 1890s - highlighted the persistent problems about the site of the prison, the conditions and state of the buildings, and the difficulties in reforming repeat offenders. In 1895 the prison commissioner Colonel Garsia summed up the feelings of many when he told a Parliamentary Committee meeting that “Newcastle is the worst prison you have got”. Although plans to demolish the prison were apparently afoot in 1895, it would take another 30 years for the Home Office to close the prison and transfer the inmates to Durham.