Prison History

Construction 1822-1828

On June 4th 1823 Mayor Robert Bell, in full regalia, led a procession of officials and commissioners from the Guildhall to a plot on the Carliol Croft, the undeveloped area of east Newcastle earmarked for the gaol. Here Bell placed a glass vase in a cavity in the foundation stone containing coins struck during the reign of King George IV. Over the stone was affixed a brass plate commemorating the event (All of these materials are now in the keeping of Tyne and Wear Museums).

The mayor then proceeded to lay the foundation stone with a silver trowel, which he afterwards presented to Mr Dobson, the architect, and addressed the concourse of persons assembled around, to the following effect: he said, “That he had then the honour of laying the foundation stone of a structure, which from the choice of its situation, and the rigid economy of the commissioners in its erection, would, he trusted, meet with the approbation of his fellow townsmen; the commissioners had, in determining upon the plan of the prison, anxiously consulted the preservation and improvement of the health and morals of those who might be confined in it; he did not add ‘their comfort’, because he saw no reason why criminals should enjoy comforts, which are beyond the reach of many honest and industrious persons”.

His worship concluded by expressing “his fervent hope, that by the system of labour, which would be adopted in the prison, and by a strict attention to the morals of its inmates, those whose fate it might be to be placed in that prison, would return to society better men and better subjects than when they first entered its walls”. This address was received with nine hearty cheers from the crowd assembled, and the completion of the ceremony was announced by the discharge of artillery from the Castle, and the ringing of the bells of several churches.

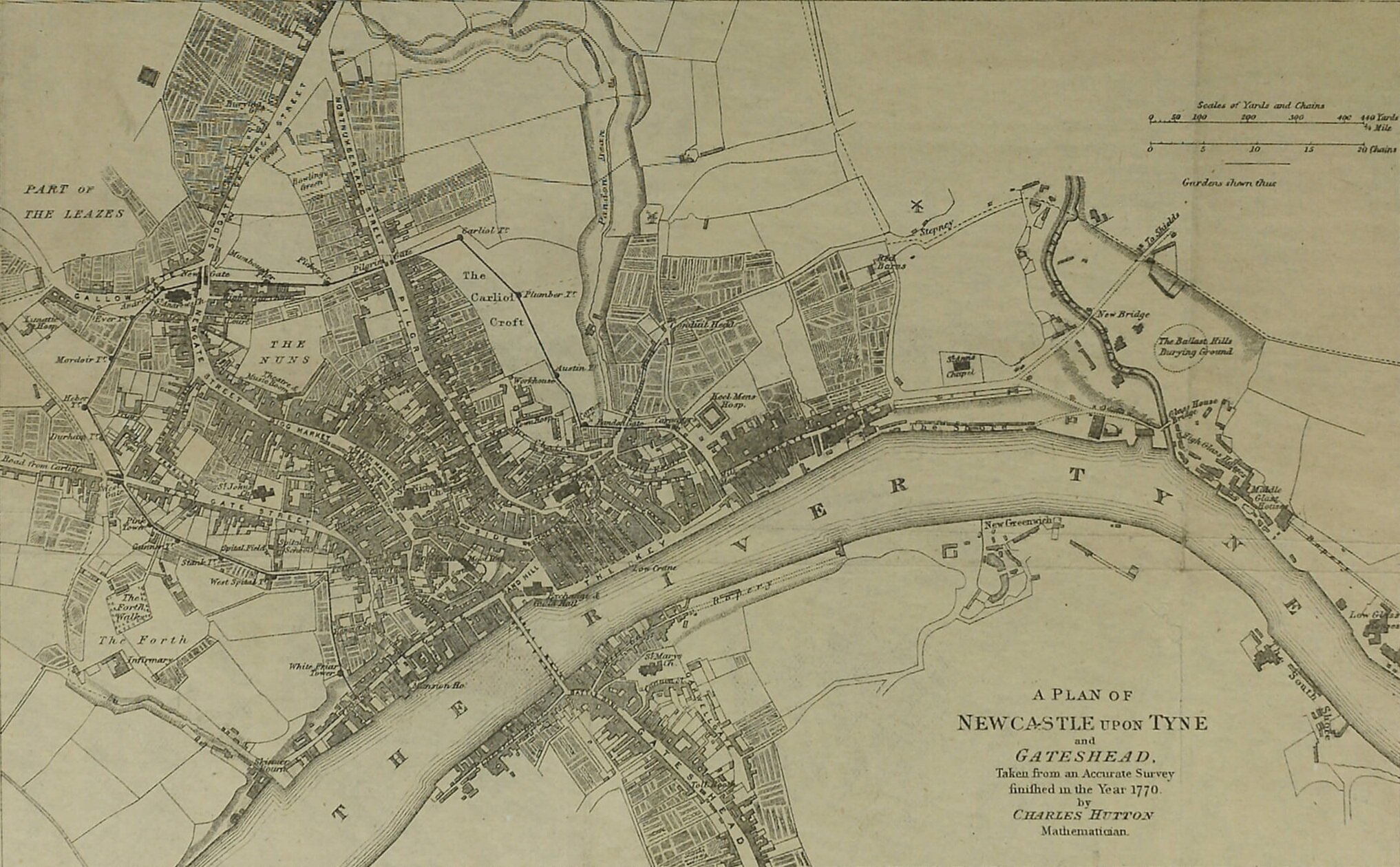

Although the Castle had been mooted as a location for the gaol, the town authorities chose to purchase a two acre site on Carliol Croft, a large portion of ground within the town walls that stretched from Carliol Tower to Corner Tower. This location made sense as a greenfield site just east of Pilgrim Street/Northumberland Street - Newcastle’s main artery - and just north of an area already hosting several related institutions, including an old house of correction, several hospitals, the Barber Surgeons’ Hall, the poor house, and a charity school. However, the plot of ground was on an incline down to the Manors and was considered clayey and “objectionable” by commentators at the time. Furthermore, the area north of the gaol was in the midst of development in 1823 with Dobson himself building a house on nearby New Bridge Street. The confined location of the gaol, with no room to expand amid the busy districts around Carliol Square, was the main factor in its unsuitability as a long-term prison.

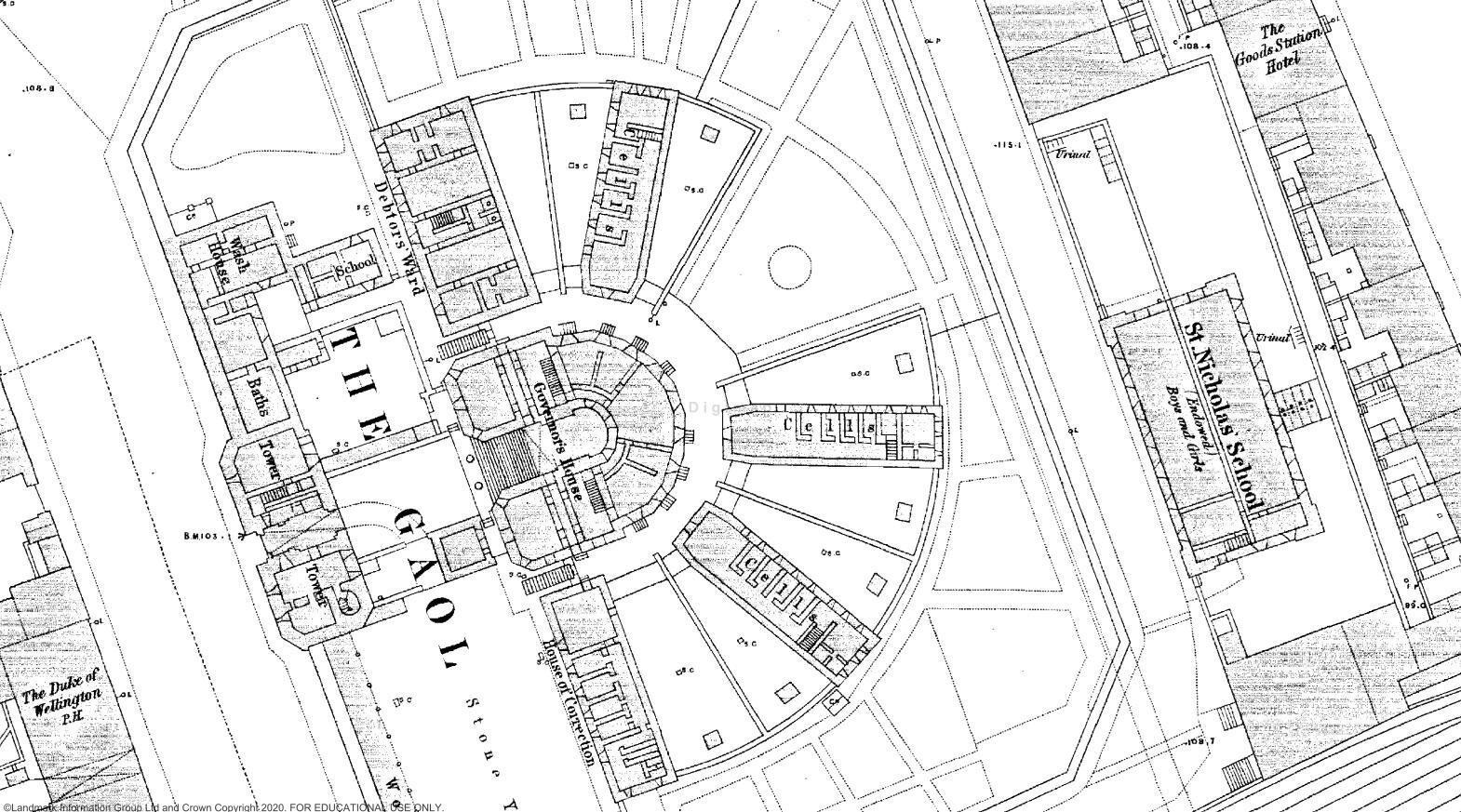

Dobson’s plan was to create an imposing structure with a fortress-style central tower, formidable arched gateway and door, and a prison containing over 100 cells where each cell would look onto the blank wall of another wing. Dobson’s plan was therefore in line with the panopticon idea and envisaged six radiating wings leading to the elliptical building in the middle. Each wing had its own exercise space, sick room, and water-closet that “can never emit any offensive or unhealthy smell”. Female prisoners and debtors were given their own wings. Prisoners would pass through boundary walls that were 25 feet high and enter the Gaol through an entrance tower with gates on the west side of Carliol Square. As we can see in his painting (below), Dobson was proud of this awesome feature which led to a grand staircase and another tower, a dramatic statement made in stone and iron. Another interesting feature of Dobson’s planning was that he consulted with “more than one burglar of celebrity” to gain information on methods they used to escape prisons. This did not, however, prevent dozens of successful breakouts over the proceeding 50 years.

“a great and beneficent revolution in prison architecture” and a “move away from the “barbarous”.

Dobson’s plan was seen by one admirer as “a great and beneficent revolution in prison architecture” and a move away from the “barbarous” era of manacles and fetters. Although widely praised, the gaol cost the enormous sum of £35,000 as Dobson was known to only use the finest materials in his constructions. In this case good quality stone was sourced locally from the Church Quarry at Gateshead Fell. Due to these high costs only five of the six radial wings were ever built and this meant that the gaol was operating at capacity almost immediately after opening, a problem not helped by the fact that it housed debtors also.

The gaol took almost five years to build and it opened to receive prisoners from Moot Hall and Castle Garth in February 1828. The infrastructure of the gaol was extensive and included wash-houses, store rooms, stables, chapel, and work yards containing a treadmill. The latter is interesting in that the system of classification which inspired Dobson’s architecture was extended to church attendance. The historian Eneas Mackenzie described the arrangement for religious services:

“The semicircular part of the fourth story contains the chapel, which will be lighted from the sides of a dome. The prisoners will be marched from the upper gallery of their own wing, across an iron bridge, to the door of the chapel, which opens into their pew. There will be nine doors and nine pews for the different classes; and the pews being divided by partitions, extending to the roof of the chapel, the view of each class will be confined to the pulpit. The altar will stand in front of the pulpit, on one side of which will be a pew for the governor's family, and on the other one for the keeper of the house of correction. Behind this, and concealed by a screen, is space for another, which may be appropriated for female debtors. The clergyman, governor, &c. will have a clear view of all the congregation in their several boxes.”

This kind of infrastructure required many staff to manage the prisoners as well as day to day operations in the gaol, and the Census of 1841 indicates that alongside the governor and deputy governor, the gaol also employed a porter, turnkey, two taskmasters, warders and wardresses, a clerk, a matron, and several domestic servants. A gaol surgeon and chaplain made daily visits to the prisoners and a schoolmaster and schoolmistress were added later. With this many staff and their families moving in and out of the grounds, it is clear that Newcastle Gaol was not only a space of punishment, but also a space of work, education, and reform. Although physically separated from the town by its walls, the inhabitants of the Gaol shared in the daily life and struggles of a growing urban centre.

Gaol History Timeline