Life Inside

Although it only had a short-lived history the gaol played host to many fascinating and tragic stories. Life Inside is a repository for some of these remarkable moments and also a collection of short and engaging articles on life in and around the gaol. These have been put together by the principal team and a selection of local experts and students.

Dissection & Bodysnatching

One of the few relics to have survived from the Surgeons’ Hall are a set of surgical instruments that would have been used to explore the inner workings of Newcastle’s dead. So why were Newcastle’s surgeons obliged to dissect some criminal corpses, and what opinions did people have about the anatomists?

The Final Executions

On the morning of Wednesday 26th November 1919, two men (Ambrose Quinn and Ernest Bernard Scott) were executed at Newcastle prison. They were to be the last two people to ever suffer that fate at the prison and although unconnected, their crimes and profiles bore many remarkable similarities.

Coroners and Crime

The coroner may not be the first person you think about when considering the people connected with a gaol. However, as the judge tasked with investigating sudden and unexplained death, to report the death to the government, the coroner visited the gaol each time a prisoner died.

All The Fun Of The Fair

A feature of prisons in the nineteenth century was their location. Not in the wilds at the edge of town, but in the centre of the community- to act as a deterrent and a warning. Newcastle gaol was organised according to the ‘separate system’, a monastic approach to punishment which, in theory, meant that within the walls ‘the utmost order and quietness’ prevailed. The same cannot be said for the area around the prison in Carliol Square.

The Barber Surgeons & the missing statues

In Newcastle the history of medical education and anatomy overlaps with the history of crime and punishment. Connecting these two spheres was the Company of Barber Surgeons and Tallow Chandlers, a craft guild which was established in 1442 and licensed generations of men to practice surgery and barbering in the town.

Judge, Jury & The Executioner

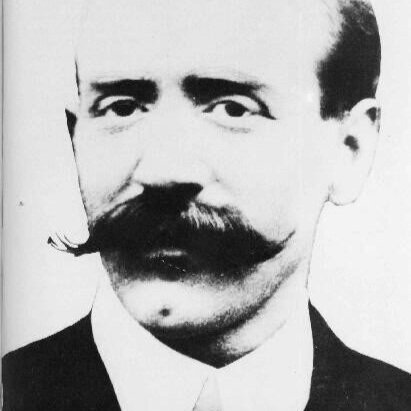

The history of hangmen is a long and complicated one and no more so than when looking at their relationship with the execution crowd. For centuries the role of executioner was a largely informal position, in some instances even undertaken by criminals themselves to avoid a harsher sentence, as was the case at the 1792 triple execution of William Winter, Eleanor and Jane Clarke. However, in the mid-nineteenth century the role was steadily professionalised and by the turn of the twentieth century it had gone from a widely deplored and despised role to a much-coveted one, which carried a sort of macabre celebrity status.

Double Execution Debut

Given the heavily restricted and private nature of executions after 1868, little information was often provided to the press to report on hangings. One place where we do get interesting historical detail though is posthumously published diaries and recollections of Hangmen. This is particularly true of one such case in Newcastle, the 1901 double execution of Uncle and nephew (John Miller and John Robert Miller).

Startling suicide!

The restrictions of prison life and confinement could often take a heavy toll and in some instances even result in prisoners taking their own lives. Although a relatively uncommon occurrence, there were numerous cases of suicide at Newcastle Gaol in its fairly short history. One particularly notable case was that of Alexander Ingram in 1911.

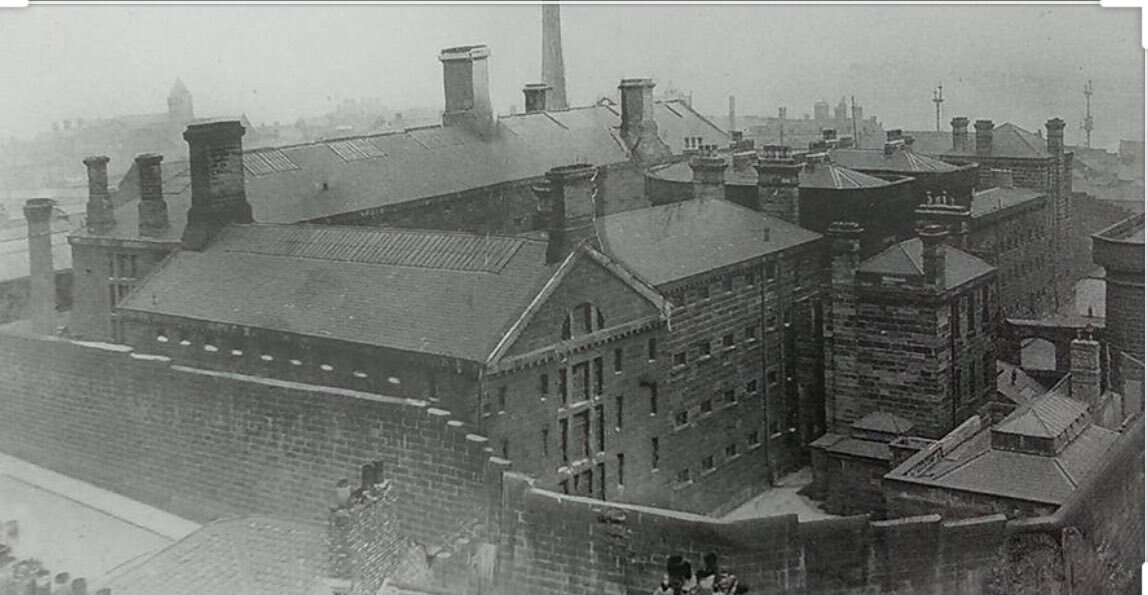

Prisons, Panopticons and Dobson’s Plans

“His designs secure all the important points in prison discipline, security, classification, and inspection, and completely guard against the possibility of combination.”

Jobbery at the Gaol

The gaol that John Dobson designed was a solid, modern, prison based on the latest trends for penal construction in the early nineteenth century. However, what was fit for purpose in 1828 required modification as the century progressed. By 1856, the gaol had approximately twice as many prisoners as it was designed for, and a significant number of these were women (400 in 1859-60). Building work was needed to alter the prison to suit changing circumstances.