Prisoners

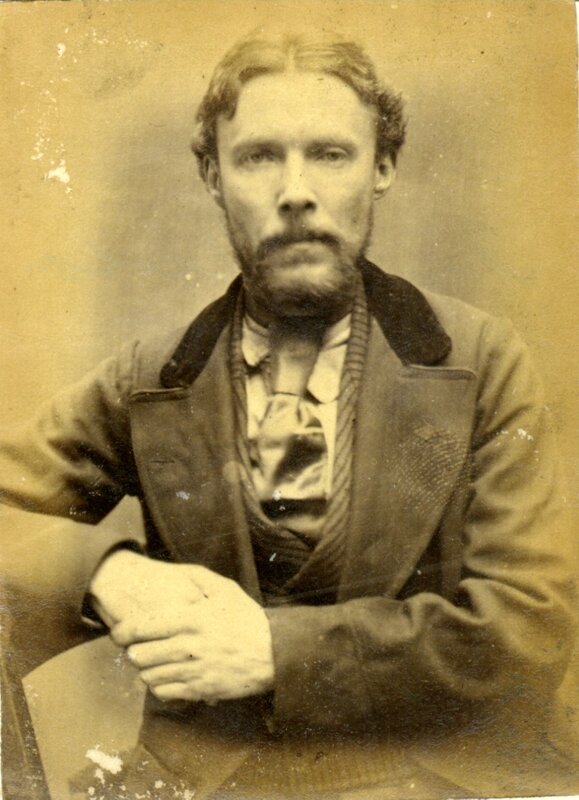

Throughout its history Newcastle Gaol housed people convicted of all kinds of offences - vagrancy, fraud, murder, rape, arson, cruelty to children, prostitution, and so on. However the vast majority of convictions were for theft of personal property, offences that would be considered relatively minor today. For example, in December 1872 three railway workers - Robert Hardy, George Ray, and Thomas Pearson, were all sentenced to four months hard labour for stealing a gallon and half of ale from a warehouse owned by their employers, the North-Eastern Railway Company. Their mugshots have survived, giving us details of their height, hair and eye colours, as well as what appear to be their fingerprints on the negatives. Although they don’t seem to have offended again, recidivism was a perennial problem for magistrates and gaolers in Newcastle. One example of a thief with a lengthy rap sheet was James Loxely, a 22 year old striker (or blacksmith’s assistant) who by 1873 had already spent a few years of his young life in gaol. In October of that year Loxley robbed another man of 15 shillings, using violence in the process, and for this he was sentenced to seven years in gaol. After serving this sentence, and aged 40, Loxley was charged with stealing lead from the North-Eastern Railway Company, although this time he was found not guilty.

Newcastle was known for its high number of female offenders, with women making up almost 33% of committals in 1865/66. Of these 514 inmates nearly half were recorded as prostitutes under “occupation” by the gaol authorities. Female prisoners incited particular opprobrium from the authorities, with one councillor calling them a “deplorable set of wretches”. Some women were incarcerated with their children and it was reported these infants shared in the gruel and bread-based diet of their mothers. The Governor of the gaol during this period, Thomas Robins, gave a speech to the British Association in 1863 where he argued that the lack of demand for female labour was one of the causes of these committals. He recommended the establishment of public laundries which “would furnish a great deal of employment for poor women, and, at the same time, be an advantage to the public”.

One of the ironies of Newcastle Gaol is that its presence did little to deter crime in its immediate vicinity. Carliol Square was known for the gaol, but also for its rough pubs and brothels; one campaigner calculated that 200 prostitutes embodied the “human flesh market” in this district. No.2 Carliol Street was mentioned occasionally in crime reports; in 1870 a drunk Norwegian ship’s captain was robbed by a pair of prostitutes in this premises, while in 1884 William Wardroper was sentenced to three months in gaol for keeping a brothel here. Wardroper was an old offender who was part of the Douglas/Preshious gang of jewellery thieves in the late 1850s and served five years in the gaol. By 1884, aged 62, he was married to a woman aged 28, and when he was released from his three month sentence he found that his wife had sold most of his goods and “took to flight”. Wardroper was incensed to learn of this and, armed with a revolver, he entered the nearby Newcastle Arms Inn and attempted to shoot the barman, Thomas Lockey. It is unclear what Lockey’s role in the matter was, but luckily for him Wardroper’s gun jammed and he was sentenced to two months hard labour. The 1901 Census records that Wardroper was single and an inmate of the Union Workhouse, Westgate Road.

Even though inmates were incarcerated behind thick and high boundary walls, communication with the outside world was possible. In the 1850s it was common practice for inmates in the stone yard to toss rocks out over the wall as a signal to confederates outside to throw in contraband. Many of these rocks either hit passers-by or damaged properties on Carliol Square. In 1859 Inspector Elliott intercepted a package thrown into the gaol - it was addressed to a female prisoner and contained some tobacco, liquorice, and a love letter. Much later, around the 1910s, a local resident named Ella Harrison recalled a “nasty sort of a woman” used to come to the walls and sing “Speak to me Thora” to her sweetheart in gaol.

“Children growing up in such an atmosphere, cannot be otherwise than criminal. When they are convicted of crime, the only remedy provided by law is the punishment of whipping and imprisonment, punishments which only render their miserable lives still more miserable, but which give them neither the desire nor the means of reformation. ”

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the gaol’s history is the number of children and juveniles imprisoned for property-related offences. As the population of the town grew throughout the 1840s, the Town Council recognised that juvenile crime was a significant problem. A Committee was appointed to investigate the matter in 1852 and their report indicated that 663 children and juveniles had been apprehended by the authorities between November 1851 and November 1852. This included 33 boys and girls aged 10 or under. The Committee pinpointed poverty, parental neglect, and abuse of alcohol as the root issues of juvenile crime:

In M’ -s entry, there are 45 families; of these 45 mothers, 40 are more or less addicted to drink; in some houses, six or eight persons may be found sleeping in one room without any separation or distinction of sex or age; the language is most obscene - the place is a picture of misery.

A.B. lost her mother when she was fourteen; her father, a drunken profligate, sold every article of furniture, and turned her on the streets. At seventeen, she was found in a dark, damp cellar in G- Street, where she had laid down to die - and in fact she died shortly after.

Children growing up in such an atmosphere, cannot be otherwise than criminal. When they are convicted of crime, the only remedy provided by law is the punishment of whipping and imprisonment, punishments which only render their miserable lives still more miserable, but which give them neither the desire nor the means of reformation.

The report recommended an expansion of the reformatory system and ragged schools to divert children away from prisons. Another method, pioneered by Inspector Elliott of the borough police, was to establish and supervise squads of young shoeblacks, to give boys an occupation and safe place to sleep at night.

However, despite these reforms, crime statistics indicate that children continued to be incarcerated in large numbers. In the 1866 judicial statistics for offenders aged under 16, Newcastle recorded six male thieves, four female “known thieves”, and four female prostitutes. The statistics also showed that 115 male vagrants and 78 female vagrants under the age of 16 had come to the attention of the police. This hints at the misery of the social conditions for many children in Newcastle who did not have a secure home or access to education. The surviving mugshots from 1873 give us a sense of the poverty and emotional exhaustion of some of these children.

Throughout this time Newcastle attracted immigrants drawn by employment opportunities in industry, manufacturing, ship-building, and mining. The 1841 Census records indicate that significant numbers of Irish people had recently settled in Newcastle, generally in the Sandgate and Quayside areas where slums predominated. This growth in their numbers exploded after the Famine and by 1851 there were 7152 Irish-born residents of Newcastle, making up 7.9% of the population. Sandgate was at the heart of the Tyneside Irish community, with the Irish making up 41% of the population in Wall Knoll Street for instance. The preponderance of young, male, rural-born immigrants to Newcastle might explain the high numbers of Irish being arrested and serving sentences in the gaol. By 1869 about 21% of arrests were of Irish-born residents, despite them representing just over 5% of the population of the town.

While the Irish were the most visible immigrant population in Newcastle’s criminal justice system, later prisoners included Germans who interned in the gaol under the wartime Aliens Restriction Act 1914. A particularly interesting case is that of a mining engineer named Otto Stalmann who had lived in Whitley Bay since 1912 and worked for the North-Eastern Electrical Smelting Company. Stalmann, who was born in Hanover but was a naturalised American citizen, gave investigators incorrect dates as to his arrival in Newcastle from London after the outbreak of the war. For this offence Stalmann was sentenced to three months hard labour, followed by a recommendation for deportation afterwards. This sentence seems inordinately harsh to modern eyes, but reflects the panic about German “spy rings”, especially in a naval and industrial powerhouse like Newcastle. Whether these spies existed or not, hundreds of foreign nationals in Newcastle became classified as “enemy aliens” during the war and many were subject to internment, curfews, and covert surveillance.

Another German named Johann Jurgen Kuhr, of 10 Sunbury Avenue, Jesmond, was imprisoned in the gaol in September 1914 for possessing materials that could be used for the manufacture of explosives. Kuhr, who was married with four children, was an engineer and inventor who worked at a chemical firm in Sunderland. He had apparently fitted out a research lab in his house as well as a wireless telegraph service, despite being denied permission by the Postmaster-General to do so. On December 28 it was reported that Kuhr had sensationally escaped from the gaol in the early hours of the morning using his bedclothes as a rope. Newspapers all over Britain quickly printed the following “wanted” notice:

Wanted, having escaped from custody from His Majesty’s prison in this city on the 27th December, 1914, John Jurgen Kuhr, German subject; occupation, engineering draughtsman; aged 45; 5ft. 5 1/2in. in height; florid complexion; blue eyes, dark brown hair; proportionate build; dark brown beard, probably now shaved off; flat footed, walks bow legged; speaks imperfect English; dressed when last seen in blue serge prison clothing.

Despite some scepticism that a quiet scientist like Kuhr had suddenly become Jack Sheppard, police scoured the district in the search for the fugitive, and all ships leaving the Tyne were inspected. On December 29th, however, it was revealed that Kuhr had never, in fact, left the prison grounds but had been crouching behind some packages in a store-room for 54 hours until the pangs of hunger, and pain of his rheumatism, forced him to surrender. Kuhr was later identified by MI5 as a spy working for German intelligence, although this has been disputed by a recent historian.