Who would be a hangman?

It is often asked of meat eaters whether they would be willing to kill an animal for their own dinner. Recent studies in America have shown that almost half (49.3%) would sooner give up eating meat than do that (with residents in some states as high as 70%). Perhaps it is not too much of a stretch then to ask whether supporters of capital punishment would be willing to undertake the job themselves. Well in 1883 a vacancy in the role occurred and it would appear that many North East residents were only too keen to apply. Their professions, perceived qualifications for the role and reasons for doing it offer fascinating insights into the culture of capital punishment in the period and the public’s interaction with it.

On 22nd September 1883, the front page of the Illustrated Police News carried a remarkable illustration, accompanied by the title ‘Applicants for the vacant post of hangman’. In the central image a room full of men are eagerly queuing in front of an official’s desk. Amongst the eager assemblage there is a monocled gentleman, top hat in hand, and other members of the professional and middle classes. The illustration’s accompanying side panels show a remarkable collection of caricatured faces, including people of varying class, race and gender with the caption ‘a few other applicants’. The contentious representations in the image could be the subject of a blog on their own, but it is the position they are in attendance for that is the focus here.

‘Applicants For The Vacant Post of Hangman’, Illustrated Police News, 22 September 1883. Image courtesy of British Newspaper Archive.

The illustration was accompanying a story reporting the remarkable number of applications that had been sent to the Home Office following the death of public executioner William Marwood, on 4th September, 1883. Marwood’s death, at the venerable age of 64, which one paper poetically described as ‘leaving a void in hempen’*, had apparently sparked a flurry of interest across the country for his job. The Home Office had been in receipt of large numbers of letters applying for the position. What is most remarkable though is that the article gives us an insight into some of the letters that came in from the North East of England. So, if ever you wondered what sort of person could hang a man, here’s a good indication for you. But first we need a bit of context on the role itself.

A prison the size of Newcastle was a significant place of employment in the nineteenth century providing a livelihood to everyone from clerks to cleaners, but one position it didn’t have on a permanent salary was that of hangman. Where once the town had had an official in the role, known as the Whipper and Hougher, by the nineteenth century the role of hangman was a much more peripatetic one and the hiring of one fell to the Sheriff on a case-by-case basis. Testament to this can be seen in the changing executioners in the early life of the gaol. By the time of Marwood’s death, in 1883, Newcastle gaol had seen 5 prisoners executed and in each case there had been a different executioner – the latest of which had been Marwood himself (officiating the prison’s first private execution, that of John William Anderson, on Dec 22nd 1875).

Despite the high fortress like walls of Newcastle gaol, news of executions spread far and wide and attracted significant audiences, filling newspaper columns in the weeks leading up to them and immediately after the events themselves. Such was the clamour around certain cases that even after 1868, when they were undertaken out of public view, thousands of people were often recorded as being in attendance despite the only visible sign being the raised black flag atop the gaol to acknowledge the dreadful deed had been done. As has been noted in previous blogs, such was the clamour around executions, particularly owing to their rarity, that it was frequently reported that the city had something of a frenzied atmosphere in the build up to and immediate aftermath of one of these events. This was particularly apparent in the efforts some made to try and see the hangman arriving into town, or catch him leaving.

So, perhaps it should not be surprising to us that there were numerous applications from local residents for the role. One other reason which may have piqued public interest was a spectacular botching of an execution that same year at Durham. In what was to be Marwood’s final execution, that of James Burton at Durham Prison, a slack rope caught under his arm and left him hanging in agony between the scaffold trap doors. He had to be hauled up from the pit and hanged all over again – to the great relief of those in attendance the second attempt was successful.

The reports from the event, including a harrowing illustration in the Illustrated Police News (see image), drew widespread public criticism and even reached the House of Commons, notably when Newcastle MP and newspaper proprietor Joseph Cowen, asked the then Home Secretary,

“Could the right hon. Gentleman not exercise some supervision over the public hangman, so that these barbarous proceedings should not be repeated? Would it not be possible to devise some more scientific mode of dealing with criminals—electricity or poisoning—rather than hanging?”

This scandal and its fallout eventually led to the Home Office sanctioned Aberdare Report, which was arguably the first serious attempt to professionalise the role and practice of hangmen.

So, we now know some of the reasons why people might have taken an interest in the role, but who were the people that actually applied from the North East and what was it that motivated them?

One such person was Henry Rigby of Trimdon Colliery, County Durham. In his letter to the Home Office he described himself as “14 stone weight, 35 years of age” and “6ft 1 in my stocking feet.” Far more remarkable though was his reason for his suitability, Rigby stated

“I would hang either brothers or sisters, or anyone else related to me, without fear or favour.”

On the 1881 census there is a Henry Rigby listed as a resident of Trimdon and working as a Coal Miner, which may be our Henry. This were very dangerous and dirty roles and Rigby would have been only too aware of the hardships of work and the proximity of life and death. Indeed, the following year previous one of the shafts at the colliery suffered an enormous explosion that saw two thirds of the men killed. The Graphic newspaper carried an illustration covering the tragedy (pictured below). However grim the task of public executioner might have seemed to some, to Rigby it may well have seemed infinitely preferable to his current situation.

Another eager applicant was one William Midgley, a chimney sweep who was ‘carrying on business at 143 Westgate Road’ (for Newcastle residents this is roughly where the Bodega pub sits today). Listing himself as 25, 5 ft ½ and married with one child, Midgely was a native of Hull who had been resident in Newcastle for the past couple of years. The newspaper reported that in his letter Midgely had made the extraordinary claim that it had been his ambition ‘from a boy to be a hangman’ and although he had no experience he was confident that ‘at the critical times his nerves would stand the test of time.’ On the subject of his nerves he included the salient fact that he was a tee-totaller and an ‘Indoor Guard to the Manors Lodge of Good Templars’ (a temperance movement founded in the mid nineteenth century). Alcohol was often the preferred nerve steadier of hangmen, with frequent reports of them requiring it to steel them for the job or sometimes being heavily under its influence at the time of officiating. When in Durham for executions at the prison, William Marwood was renowned for regaling the public with tales of executions whilst propping up the bar of the nearby Dun Cow Inn (his residence of choice prior to executions).

What makes Midgely’s application particularly interesting is the detail he gives regarding execution procedures. Given that public execution ended in 1868, it is reasonable to assume that he may never have attended anything other than a private execution (so cannot have seen the procedure). Despite this, he talked about wanting to use the ‘scientific method’ (an allusion to Marwood’s famous ‘long drop’ technique, which calculated the length of the rope and ‘drop’ required based on the weight and height of the condemned prisoner). He also professed to knowing all about the ‘pinioning process’ (the procedure by which the prisoners’ hands and ankles were bound prior to the noose being placed around their neck). This is a good indication of the level of detail provided by local newspapers and known to the general public from accounts of the executions in the period.

Another applicant was one Bill Vokes, a bill poster operating in Sunderland, but perhaps the most remarkable of all in the region was a man named ‘Scholefield’. Described as a ‘tall, stalwart man of some fifty or sixty years of age’, Scholefield arrived unannounced in the offices of a London newspaper, mere hours after the telegram announcing Marwood’s death had been received. He said that he had made haste for London as soon as he had heard of Marwood’s illness. Scholefield told the assembled reporters that he had an invention to show them. He then pulled from a black bag a ‘horrible looking instrument in hemp and brass’ proclaiming,

"Here is the invention that is wanted; it is perfectly simple; anybody can hang a man with that. I invented it years ago, and it is absolutely certain. I have tried it over and over again. and never found it to fail yet. When I saw all the papers writing about the cruelty of the long drop, I couldn't rest; I am only a working man, and I don't want any money for it, but I've travelled 300 miles in order to bring you the invention, so that you may see with your own eyes exactly what is wanted."

When pressed on what had driven him, he mentioned a report in the Pall Mall Gazette detailing the horrible scene at James Burton’s Durham execution earlier that year.

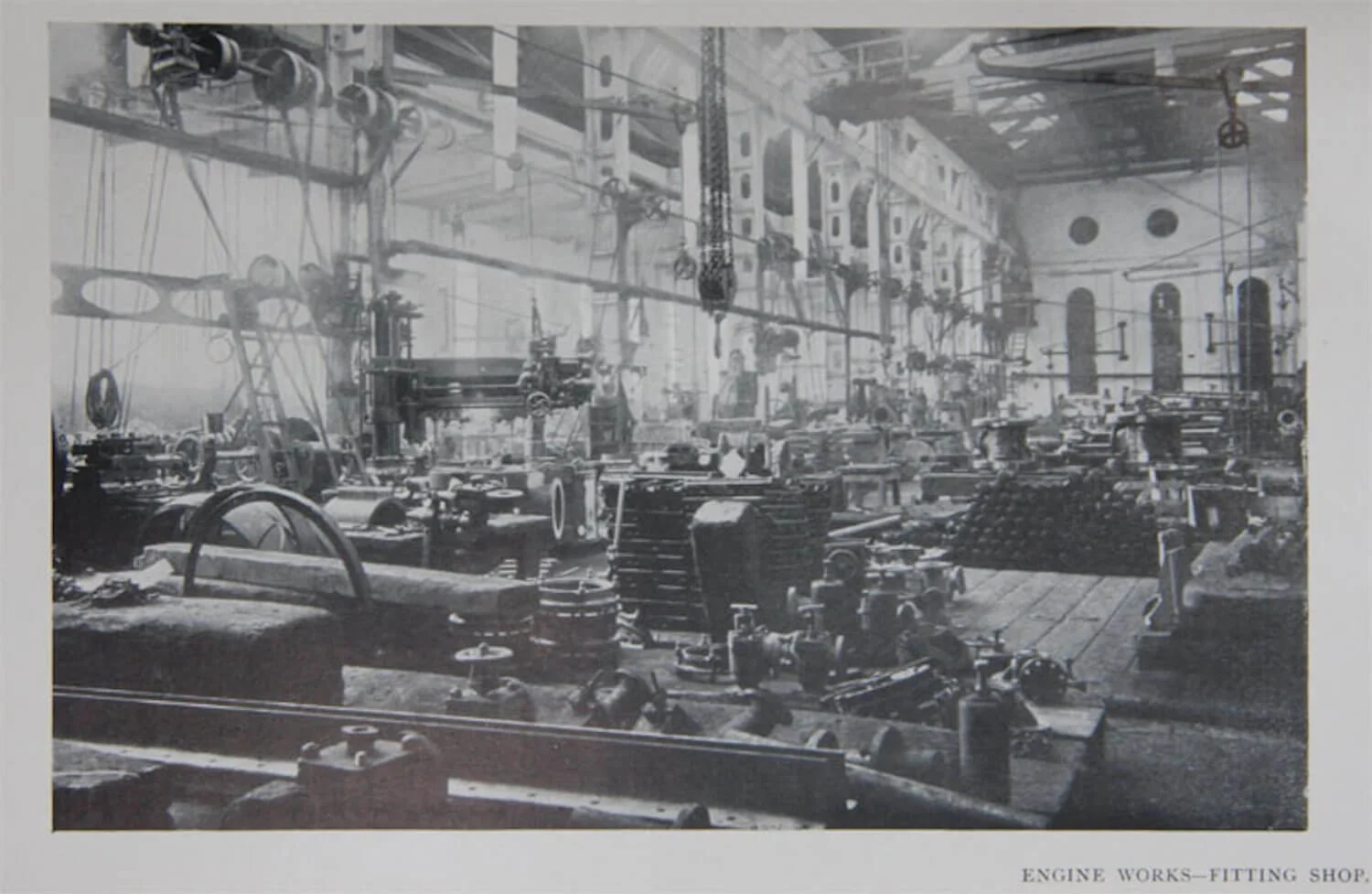

Without access to the letter itself we cannot be certain of who exactly ‘Scholefield’ was, but the report mentioned that he was employed at Palmer’s Shipbuilding Yard in Jarrow. The 1891 census has a Frederick Scholefield, residing in Jarrow and listed as 62 years of age and working as a stationary engine fitter – a common role at the shipyard. If this is indeed the Scholefield in question then as an engine fitter at Palmer’s Shipyard he would have been working in the ‘Fitting and Brass finishing shop’ (see map below) which would have given him daily access to the working materials and the fine working, practical knowledge needed to create such a contraption.

Images from left to right: 1900 view of the Engine Works & Shipbuilding Yard Departments of Palmers Shipbuilding & Iron Company (part of a view of Palmers Works). Image courtesy of Philip Strong’s Lane Family Archive - Engine Works Fitting Shop - Palmers (undated), Image courtesy of Grace’s Guide

As in the case of Midgely, Scholefield professed a good working knowledge of the hangman’s trade, including details such as the preferred rope thicknesses of Marwood and other hangmen. A further testament to the wider public interest and knowledge of the procedures of execution. His motives however would appear to be in line with many of the later adaptations to execution, driven largely by the desire to make it as painless as possible. Before he left the newspaper, heading straight for the Home Office with his invention, he told the assembled journalists that,

“In the cause of humanity and civilisation I appeal to you to secure the adoption of this humane invention.”

We can only but wonder what sort of reception, if any, he got at the Home Office.

So, if you ever find yourself wondering what kind of person had it in them to hang another human being, look around you, they may be closer than you think.

Notes:

*Hempen – (hemp was a key component of the rope used for his hangings) to see a hangman’s rope from the period see https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co155246/hangmans-rope-england-1870-1888-hangmans-rope