The Last Woman Executed

The first prisoner of Newcastle gaol to meet their death on the gallows was Jane Jamieson in 1829, often recorded as Jamieson. She was also to be the last woman hanged in Newcastle and suffered the further ignominy of being the last prisoner of Newcastle to be publicly dissected, an additional punishment for the crime of murder until 1832. It may well be for these reasons that she has had such a lasting presence in the ephemera and histories of Newcastle and, if some ghostly reports are to be believed, still does - of which more later.

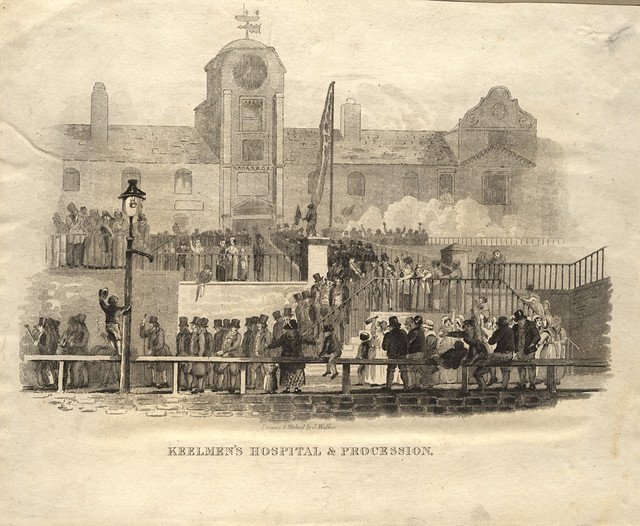

Jane was a fish hawker who plied her trade in and around the Quayside at Newcastle. Her mother, Margaret, was a resident at the Keelmen’s Hospital on the New Road (an almshouse established in 1701 for poor Keelmen and their widows – it still stands today, on what is now City Road).

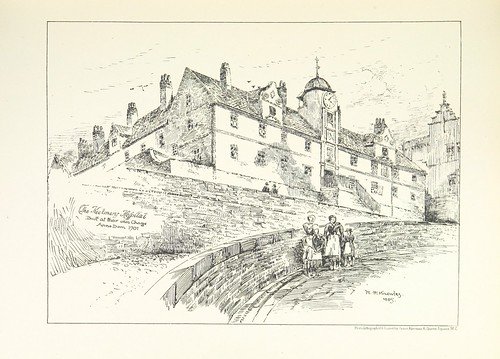

A selection of representations of the Keelmen’s Hospital over the last two hundred years. Images (from left to right): Keelmen’s Hospital c.1800 artist unknown - the hospital depicted in 1895 by W.H.Knowles - a photograph of the central courtyard with landscaped garden in 1961 and a photograph of the building as it stands today. Images courtesy of Co-Curate and Newcastle Libraries.,

In the early hours of the 1st January, 1829, a Keelman, William Ellison (known to Jane and others as “Bill Elley” and according to some reports an occasional lover of Jane) arrived at Margaret’s with a ‘gill’ of rum and shared it with them both, to see in the New Year. The following day, 2nd January, around 2pm fellow residents of the Keelmen’s Hospital heard an argument between Jane and her mother. In evidence given at her trial, Ann Hutchinson (daughter of one of Margaret’s neighbours, Jane Hutchinson) claimed that she heard Jane and her mother angrily arguing, reporting that Jane called Margaret an “old lousy, stone naked kill-goodman b-----r.” to which her mother replied, “No, you whore, I did not kill my man, but you killed your two bairns.”[1] The next reported noises were of a distressed Jane crying out “Oh my mother”. On entering the room neighbours found Margaret bleeding from a wound in her chest, seemingly induced by a poker found near the fire.

Despite the severity of the wound Margaret did not die immediately, but over the next ten days her health dramatically deteriorated, and, despite the efforts of several visiting surgeons, she died on the 12th January. In the days between the infliction of her wound and her eventual death, numerous rumours spread around town as to the nature of her demise with word getting round that she had been murdered. This was complicated by conflicting reports from both Jane and Margaret herself. In the immediate aftermath of the attack Jane, when questioned by a neighbour over the incident, claimed that “I did not kill my mother, Billy Elley killed my mother.” She said that he had kicked her in the chest and the wound was owing to the force with which the “neb of his shoe” had hit her. However, in evidence at the trial numerous witnesses noted that Margaret initially had said that “Jin had done it with a poker.”

As Margaret’s health worsened it would appear that her story changed. Soon both Margaret and Jane were claiming that Margaret had been teasing oakum by the fire and fainted from the heat, landing on the poker. We cannot truly know why her story changed but it would seem that, despite the viciousness of the attack, Margaret had realised the potential deadly consequences for her daughter and moved to help concoct an alibi that might save her. It was not to be however, as numerous medical men who visited the patient and the scene attested to the unlikelihood of such a wound being induced by anything other than force. Also, Bill Elley could account for his whereabouts and other witnesses confirmed that he had not been there at the time.

Group of keelmen playing cards; Undated. Image courtesy of Newcastle Libraries Flickr

Jane’s trial took place on 5th March, 1829 and attracted great public interest with the court, Newcastle’s Guildhall, reportedly crowded in every part. After 7 hours of evidence and a 25-minute deliberation by the jury, she was found guilty of her mother’s murder and sentenced to be hanged by the neck until dead and her body thereafter sent to the Surgeon’s Hall for dissection. One of the many cruel ironies of Jane’s case was that she would have known the Guildhall only too well as in 1826 the Fish Market was moved by the Corporation from Sandhill to under the columns of the Guildhall. Just three years later her fate would be sealed just above where she daily plied her trade.

Fishwives trading on the of Neville Street & Forth Street 1890. Image courtesy of Co-Curate

In his 1827 history of Newcastle, Eneas Mackenzie remarked on the new market as ‘one of the handsomest architectural ornaments of the town’. He thought that it ‘has cleared the Sandhill of the lumber of fish stalls, and widened the entrance to the Quay, which before was inconveniently narrow.” But it would appear that the fish hawkers themselves were far from pleased, by the move, which may give us a clearer insight into how Jane felt about it. Testament to this can be seen in a contemporary ballad railing against the enforced move, entitled The Fish-Wives’ Complaint, which had the following verse,

It's nee use being iv a rage,

For a 'wor pride noo fairly sunk is

Ye've cramm'd us in a Dandy Cage,

Like yellow-yowlies, bears and monkies.[2]

The ‘dandy cage’ was a reference to the Guildhall’s Doric columns (still visible today) from which the traders now operated behind – perhaps an early foretelling of Jane’s short time behind bars.

Images of the Guildhall; (From Left to Right) The Old Fish Market, Sandhill, Newcastle upon Tyne - Henry Perlee Parker (1795–1873) Image courtesy of Laing Art Gallery - ‘Guild-Hall or Exchange, Newcastle On Tyne.’ Print, lettered with title and 'Drawn by W. Westall, A.R.A. Engraved by E. Finden. Published by Charles Tilt, 86 Fleet Street, London, 1829'. Image courtesy of the V&A - The Guildhall, 2019 (image courtesy of Co-Curate).

As was so often the case in murder trials in Newcastle, alcohol played a major part. Numerous records note Jane’s, and to a lesser extent her mother’s, proclivity to drink and in several places it was recorded as the ruin of Jane both spiritually and physically. One surviving ballad detailing her trial recorded that,

“she was formerly a smart, clean good-looking woman; but lately she has been little less than an object of disgust. She had given herself up to the most dissipated habits, and appeared to be in the full enjoyment of all their deplorable consequences.”[3]

John Sykes’ 1833 history of Newcastle describes Jane in similarly derogatory terms as “a most disgusting and abandoned female, of most masculine appearance, generally in a state of half nudity.” He went on to detail her clothing at her trial, as if to emphasise her normal state of degradation, “she perhaps never was so decently dressed as when upon her trial, having on at that time a black gown, black hat and green shawl.”[4]

‘Jane Jamieson as she appeared at the Bar March 5th 1829) on her trial for the murder of her mother.’

Her eventual send-off was estimated to have brought 20,000 to the Town Moor to witness it, with over half of those present reported to be women. This was, no doubt, in part owing to the rarity of seeing a woman executed, the last to have suffered that fate were Eleanor and Jane Clark in 1789 (prisoners of Northumberland - hanged outside the Westgate Walls).

Jane was processed from the gaol on the morning of Saturday 7th March, through the principal streets of the town to the site of the gallows on the Town Moor, just N.W. of the army barracks (very close to where BBC Newcastle sits today). She was conveyed in an open cart carrying her coffin, which she sat atop, and, in order to avoid the gaze of the watching crowds, she closed her eyes the entire length of the procession - some 45 minutes. On the gallows, seconds before her grisly end, she uttered the words “I am ready” and with that she was launched into eternity. Records show that the execution and procession cost £28 3s 3d, £3 - 3 shillings of which was given to the executioner.

As was customary, her body was left to hang for an hour and she was then processed to the Barber Surgeon’s Hall for public dissection, where her clothed body was on public display in the grand entrance until 6pm that day.* Lectures were given on her brain and body for the two weeks following her death, administered by Surgeon John Fife (later Mayor of Newcastle). They were free to attend for all medical men and available for a small fee (10 s 6d for the 2 week course and 2s 6d for a single lecture) to members of the public.

The lectures were attended by a local apprentice Surgeon, Thomas Giordani Wright, who wrote in his diaries that, ‘they may be very useful to the tyros of the profession and highly interesting to a general audience, but they do not contain any information as anatomical lectures.’ He added that Fife’s ‘manner of delivery is so deliberate and slow that the whole of his orating…might easily be compressed into one third or a quarter of the time it occupies.’

It is not clear where Jane’s body was eventually lain to rest, but we do know from surviving archival records, that it was not unheard of for the Barber Surgeons to gift the bones to fellow colleagues. So, Jane’s body may have had no eventual resting place. Perhaps this would explain why she continues to fascinate many local historians and populate so much surviving ephemera. It would appear that Jane had many afterlives.

Reporting on capital punishment in 1851 the Gateshead Observer recorded the ‘not generally known’ titbit that the Landlord of a ‘low tavern in Newcastle’ had purchased Jane’s ‘nut-measure’ (most likely a small wooden tape measure) following her death and would hire it out as a dice box to customers for a fee! Although no other record of this exists, it was not unheard of for people to try and purchase, amongst other things, the clothes of the executed and, perhaps more commonly, pieces of the noose rope. Further testament to the ongoing public interest and fascination with Jane long after her death, can be seen in the numerous ballads and songs that survive from the period that are about Jane herself. Perhaps the most famous is the Sandgate Pant, a ditty recalling how Jamieson’s ghost haunts the Pant (an old water fountain that stood on the Milk Market). In the ballad Jane is often spied by drunken boatmen and keelmen, the worse the wear from ale, selling her wares and crying of her cruel fate.

“She waits for her lover, each night at this station,

And calls her ripe fruit with a voice loud and clear;

The keelbullies listen in great consternation

Tho'snug in their huddocks, they tremble with fear!

She sports round the pant till the cock, in the morning,

Announces the day — then away she does fly

Till midnight's dread hour - thus each maiden's peace scorning,

They start from their couch as they hear her loud cry

Fine Chence oranges, four for a penny !

Cherry ripe cornberries - taste them and try!”[5]

So, next time you find yourself three sheets to the wind on Newcastle’s Quayside, be warned – nothing good can come of following the haunting voice of Jane Jamieson.

More from Life Inside

Notes:

[1] Newcastle Courant, 7th March 1829.

[2] The Newcastle song book; or, Tyneside songster, being a collection of comic and satirical songs, descriptive of eccentric characters, and the manners and customs of a portion of the labouring population of Newcastle and the neighbourhood. Chiefly in the Newcastle dialect. p.71. See Here

[3] Account of the execution of Jane Jamieson who was convicted of the wilful murder of her mother, Margaret Jamieson, at the Assizes for Newcastle, on Thursday, March 5th, 1829, and suffered on the scaffold, on Saturday, March 7 (William Boag, Newcastle)

[4] The full text of John Sykes’ account is available at Archive.org

[5] The Newcastle song book, p.324. See here

*For more information about Jane’s dissection by the Barber Surgeons see Dr Shane McCorristine’s piece here.